The dancing boy with decayed teeth has been on the Shantipath all this week selling flowers. Yesterday he sold baby’s breath. But this morning he was selling Indian national flags, shouting ‘Freedom! Freedom!’.

Farida never understood flowers. But, today, she opened the shutter because she knew a thing or two about freedom. Freedom, like all things fragile, had made a brief appearance in her life.

She gave twenty rupees to the boy who sold freedom and asked, ‘What’s your name?’

The boy looked into Farida’s eyes through the dusty strands of hair that had fallen across his mountain-coloured eyes as he threw the flag into the car and ran away. Farida watched him disappear behind the jam-packed vehicles wondering how sometimes, a name can be the hardest thing to say.

*

The next day, the boy was still selling freedom, walking back and forth through the traffic because the Independence Day of India was only a week away. He had missed a button in his faded yellow shirt and his bare feet were creating dust whirls on the ground. Farida smiled at him from inside the car. She did not want another Indian flag; sometimes even too much freedom is too difficult to handle.

When Farida did not open the shutter even after several knocks, the boy slid his hand into a side pocket in his pants and pulled out a few packets of camphor balls.

Farida said ‘No’, shaking her head.

The boy then thrust the camphor ball packets against the shutter because he was sure Farida needed camphor balls. Farida shook her head again and looked away. When the traffic light turned green and the vehicles at the front started honking and moving forward, the boy looked at Farida with eyes that looked betrayed. Betrayal. She knew well about betrayal too.

Just then, she heard someone whisper in her ear that this was how the eyes of her child looked like when she failed him for a third time – the child to whom she almost gave life.

Yes, her child would have been of similar age, had she not failed him the first time, perhaps even a year or so older. Farida felt her heart going up in flames. Every organ in her body was burning. She knew well about burning too. And suddenly, the eyes of a woman who rested her head against a hospital door one dawn and fell to the ground speechless, knowing not what words to wail with, flashed before her. A woman in a light blue bed jacket, a floral cotton cloth wrapped around the waist, and even a jasmine-scented napkin, but no child.

She felt the flames surging up her throat, and the air she breathed felt heavier. When she finally breathed out condensed air through layers and layers of flimsy images of herself alone on a hospital bed – the exhaled air, warm and strained – she wondered if that was how sighs were made, regret hobbling through images of pain. Her heart was now melting and pouring all over the Shantipath. Farida quickly pulled a twenty rupee note from her wallet and pressed the button to open the shutter. But it was too late. The car was already moving.

As she was driven forward with the traffic, Farida watched the boy still looking at her, standing in the middle of the road, desperate and betrayed. She watched the blaze in his eyes flaming into a raging fire behind him which was stronger than the one inside herself. Was it fire that she smelled through her nostrils? She was certain it was. She had betrayed another child.

Farida knew a little about fire too. Some fires, she was told, were invisible, and you were seen dancing when you were only gasping for air.

*

The next day, on the way to the Sri Lanka High Commission from the High Commissioner’s Residence, Farida had a twenty-rupee note folded between her fingers even before entering the Shantipath. She was determined to give it away. But, as the car moved along the tar road through the traffic, she could not see the dancing boy who sold freedom.

Everyone else but him was there – the boy with long hair who played a wooden flute and danced with the girl who had a birthmark that looked like a perfectly-positioned bindi on her forehead, the man with a multi-coloured band around his head selling carpets, and even the little boy with colouring books who came only on Wednesdays. There was an old woman chewing betel who was selling flags, with the pallu of her sari wrapped around her head, but the dancing boy was nowhere to be seen. As the car drove towards the end of the road, Farida felt an emptiness taking over herself. She was disappointed. She knew too much about disappointment. Some regrets, she had learned, were never to be cured, but meant to appear and reappear and burn you till the end of your life.

The previous night, as she went to bed, the fire the boy who sold freedom had started in her heart made her stare at the rotating wings of the ceiling fan that flashed before her – all the scenes she had forcefully shut away in a suitcase lying under her mother’s bed back in Sri Lanka; A girl-turned-woman surprised at being able to fit everything she owned after ten years of marriage into a medium-sized suitcase; a bedroom wall, deaf to all the insults thrown at her, like stones tossed at a nude woman because it had been decided that she was not destined to be a mother; a husband she once loved calling her worthless, and she believing it with all her heart.

The foetus of her child was just four months old when she lost him for the first time. So tender. She was sewing yellow roses on a small baby dress when her child decided to leave her one evening; so long ago, when she used to love flowers. It was on that night, her husband Ahmad started drinking alcohol for the first time. It was wrong; so it was all her fault. He was not a man of many words, but the first time she told him she was with child, he said he hoped it was a boy, and that he would be moon-eyed like himself. Although a part of Farida was terrified and wondered what she would do in case the child was a girl, she was happy she had given him some hope – a glistening flame of light to brighten their gloomy home. She did not love him the way Rekha loved Amitabh Bachchan in the movie Silsila, but she liked seeing a smile on his face once in a while.

One year later, the second time she lost the child, Ahmad did not speak with her for three weeks, and she couldn’t comprehend which hurt her more, losing her child or losing the faith her husband had in her. Did he not know she was as helpless as he was because it was the child who had suddenly decided to leave? Even after she had already decided his name.

Even after she had planned which flowers they would plant together in the backyard until Ahmad came home in the evening after closing his grocery shop. But somewhere deep down, Farida was certain that it was somehow her fault. Every night she fought with that thought and went to bed, someone whispered in her ear in her sleep, that it was through her fault, through her fault, through her most grievous fault – in the same rhythm of the prayer they iterated over and over in the Catholic church next door during mass. Therefore, when the child came to her again months later, hopeful, that he would be safe in her hands at least this time, she promised Ahmad with all she had that she would not fail him again.

Not the child, not him, and not herself.

But, she did. So, the third time she lost her baby, Ahmad, drunk and angry, threw the small

colour television at her. It was daybreak, the time dew drops were fading before sunlight and she was not sure whether the blood under her feet was those from the cuts of the glasses or the tears of her slowly dying child. One week later, he asked her to leave his house and she only wondered what she should carry back home. She remembered crying, holding onto the beige bridal dress and the hijab which she decided to leave on the bed she had shared with the man she shared her life with; she always thought it was too puffy for a girl who was of ordinary height.

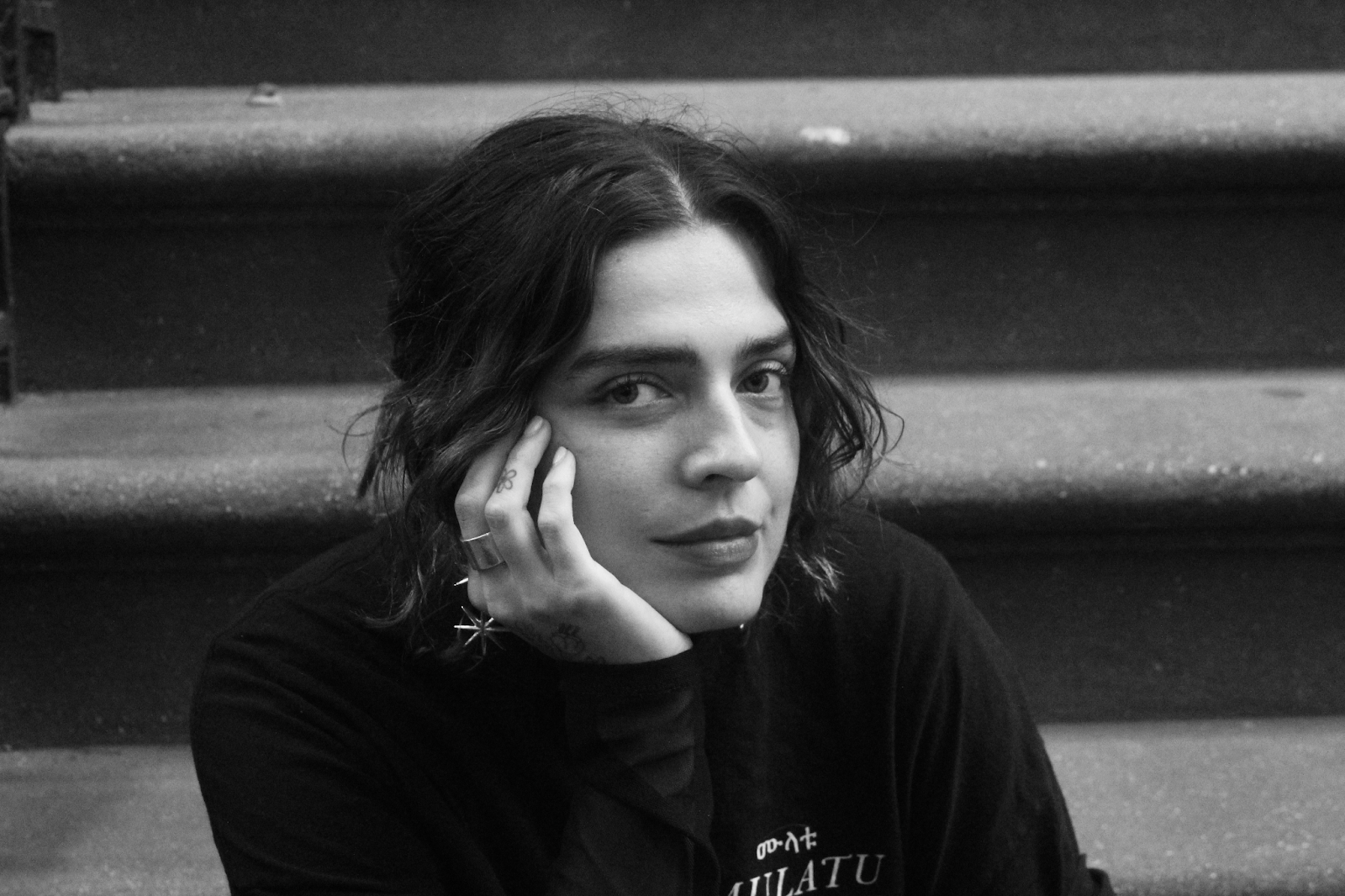

When she came back home with a suitcase one night, she was not the girl who left home as a bride. She was a wife who had left her marital home; a woman who was rejected by the man she loved; a mother who had lost her child. She was many things, but, she wasn’t exactly sure whether she could call herself a mother for she did not have a child. It changes you differently when a child refuses to be born to you. Three times. It breaks your soul when he rejects you. Three times. Farida meant precious pearl, her grandmother used to say. But she was a fake pearl irreparably shattered into grit, with pieces thrown all over a gravel road. She stared out the window several nights trying to recall the last day she remembered being happy. When it was already daybreak and she could not remember any such moment, she wondered whether she could consider herself a living human being, whether she was even breathing, if her soul was even there anymore in her gradually weakening body. Her palms were coarser, and there were dark circles around her eyes.

But they were not as dark as the darkness in her mother’s eyes. If her father was alive, she would have run to him and told him that it was not her fault; she would have affirmed and reaffirmed that she did not wish for any of it to happen, like the time when she was six years old she swore that she fell into a puddle and ruined the only good uniform she had because the girl behind her pushed her. That all of it was out of her control. And her father would have believed. But her mother has never been on her side.

That is why, when her cousin told her that the newly appointed Sri Lankan High Commissioner to India, the famous Mr. Hameed was looking for domestic help, preferably a Muslim girl from the East who could cook, she said she was interested. Farida knew she could not overstay her welcome at her mother’s home because sometimes, even mothers prioritized their repute over the flames of a daughter’s smouldering life. She left the country in a month.

Her life here was different. She smiled a little more and cried a little less. But on some nights, as she stared at the night sky from her room in the High Commissioner’s Residence, the stars formed into the pattern of the yellow roses she carefully sewed on the little baby dress when she was with child for the first time, and reminded her of everyone she had failed in life - her father who wanted to see her become a teacher, her mother who wanted to be a grandmother, Ahmad, who wanted to have a moon-eyed son, and her child who just wanted to be born. Failure, perhaps, was what she knew best in her life.

But Farida was determined not to fail High Commissioner Hameed. He was kind to her and his family considered her a part of theirs. The High Commissioner’s daughter Shazia was a drop of sunshine. She called her Akka, which meant sister; Farida had never been a sister in her life. She liked having someone to laugh with when the gardener danced around the flowers singing ‘Kisi ki muskurahaton pe ho nisar....’, pretending to be Raj Kapoor. The market day was her favourite day of the week; every visit to the market was a new adventure for a girl who had never been away from her hometown even for a day.

She had now mastered the art of buying vegetables without speaking a single word. Her only goal was to cook meals with the Khari Baoli market spices and create dishes with a taste closest to home. Her duties were clear and easy. She had to cook and keep the Residence clean. It was not hard to do. And they paid good money for it. She did not realize it at first, but when the money got deposited to her bank account month by month, and she had enough money to send back home and still buy all the jhumka earrings she liked at the Sarojini Nagar without asking money from a husband, she started feeling braver little by little. She even wondered whether that was what they called freedom back home.

High Commissioner Hameed was not a proud, self-absorbed diplomat like he was trained to be. He enjoyed listening to Farida’s stories from her hometown Kattankudy located on the Eastern border of the island during lunch every day. He who was born and bred in the lavish Colombo Seven and further educated in the United Kingdom, found the rustic, salty life in the East quite amusing. But that day, as Farida arranged his lunch looking down, silently dishing out the chicken curry and the brinjal pickle, the High Commissioner asked if she was alright.

‘Yes Sir, all fine’, she lied to him for the first time. Had she started failing him too? She wondered because failure always began with a lie – no, I did not meet Ahmad after class – no, I feel better this time, unlike the last pregnancy.

On the way back home after the High Commissioner finished his lunch, Farida’s eyes still looked for the dancing boy with dusty feet. But he was nowhere to be seen. Her eyes welled with tears for no reason. It happened sometimes, especially in the cold evenings when the sun set in tangerine hues beyond the India Gate making the whole of Delhi mourn for something nobody knew about, and on the nights when little children in sparkling attire lit lamps along the walls and the railings in the entire city, with smiles gleaming brighter than lamplight. It was the ninth time Mohandas the driver had seen her crying in the back seat.

She counted. Number nine is known to be ruthless.

‘Homeless beggars! Such a plague.’ Mohandas said aloud. Farida felt bad because she knew something about homelessness too.

Farida felt a tear rolling down her cheek. She did not know why she was this upset. She knew her twenty rupees would not have saved the boy. But perhaps it would have saved her.

*

On Thursday, the lunch hour traffic was slow, or so it seemed, because the boy Farida wanted to see was still nowhere to be seen. But Farida felt calmer with every saffron yellow Indian magnolia the car passed on either side of the road. Her fire was slowly settling down.

Farida served the High Commissioner his favourite dish that day, creamy prawn curry with moringa leaves. She was happy he finished the whole dish and called it ‘A brief visit home’.

So, on the way back home after the High Commissioner’s lunch, Farida was feeling content.

She even saw a faded rainbow in the sky. The yellow tulips beside the road looked like the tulip field Rekha came running through to Amitabh Bachchan in Silsila, which she watched over and over again as a young girl because it was the first time she saw tulips. Looking at the spectrum of pastel colours in the sky over the mustard yellow sari of tulips, she wondered how simple is happiness sometimes, though retaining it seemed the hardest thing to do.

Farida was going through the pages of the High Commissioner’s book kept on the back seat titled The Country Without a Post Office by someone called Agha Shahid Ali, when a boy suddenly appeared behind the shutter and smiled with decayed teeth, waving an Indian flag and dancing to a rhythm through the traffic. Farida sddenly felt her heart galloping.

She quickly opened the shutter and gave him twenty rupees. ‘What’s your name?’ She asked. She wasn’t sure if he remembered her face.

The boy shyly smiled and scratched an eyebrow.

‘Name?’ She asked again and the boy shook his head to either side, which could have either meant he did not understand what she said, or that he did not have a name.

‘Nadeem’, she whispered. The name she wanted to give her child. A nadeem was what she wanted – a confidant, a companion in life. It had been some time before she was able to bring herself to say the name out loud again. Nadeem, she repeated several times.

Mohandas was giving her a disapproving stare through the mirror, but she did not mind because Nadeem’s eyes were too glass-like to ignore the galaxy patterns inside them. To her, they looked more Indian than the flag he was holding, more authentic than the conversations about Bharat, High Commissioner Hameed had with important people in Nehru jackets and Kalamkari silk saris before the two country flags in the meeting room with sofas that were too good to sit on. The glass-eyes looked more real. Like something you could hold towards the sun and watch the beautiful blend of colours dancing inside it.

‘Hungry?’ Farida asked, gesturing the act of eating with her hands.

He nodded and her heart sank with more weight than a landslide that had recently buried an entire village back home. She took a bottle of water from the car door and gave him. It was all she had. The next second, when the traffic lights turned green, Nadeem smiled with her and waved at her car as it moved forward. She felt lighter as the car drove away from Shantipath and she wondered whether it was because she left a small part of her inside his glass eyes.

*

On Sunday, Shazia wanted to go to Old Delhi to shop for a shalwar kameez. With talking eyes and lips that are the colour of pink hibiscus, she was as pretty as her name, which meant Farida had to accompany her as a part-friend-part-bodyguard. A woman could never be too safe.

They rode the busy streets of Chandni Chowk in a rikshaw and Farida felt as if she was in a Bollywood movie, passing through the crowded markets where the girl always met the boy, who with his bewitching eyes made the world stop for her, sometimes for a second,sometimes for an entire lifetime. Watching Shazia pinching her, every time a fine-looking boy passed them on the street and giggling together like schoolgirls, she thought perhaps, this was what happiness felt like. It was fulfilling to have someone to laugh with over things that felt as light as sunshine.

They passed small shops with anything and everything from Indian sweets and spices to handmade sandals until they stopped at the street adorned with shimmery shops displaying stone-studded lehengas and saris, like awards in an artist’s house. As they walked through the designer dresses into a sandalwood-smelling private room, Farida thought how even her bridal dress was not as elegant as the soft hand-knotted Kahmir carpet that pampered her feet. And suddenly, leaving her bridal dress behind did not feel so tragic. Sending her fingers along the stacks of colourful fabric, Farida thought about the fine balance of the glitter and the gutter in this country, whereas back home it was either glitter or the gutter, with no space in between.

Perhaps it was the contrast of the heavy embroidery on a designer sari against the betel spits on the brick road, the fine details of a block print of a shalwar fabric against the mud-soaked carpet of a pani poori stand that made this new home of hers a fine blend of extremes in life; a place where home and homelessness did collide; a place where a woman who had lost everything could feel the lightness of sunlight.

Shazia chose a turquoise shalwar kameez with pink and white flowers embroidered into a pattern. When the salesman made her stand on a platform, helped her into the shalwar, and put the dupatta over her shoulder like a stash of a woman who had been crowned the most beautiful, her eyes gleamed brighter than the silver of the embroidered threads in the fabric. The shimmer in her eyes looked familiar. It was glistening. Almost glass-like.

Farida asked Shazia if they had time to go to the Daryaganj Book Market.

‘Of course!’ Shazia said, getting into the rickshaw. ‘I didn’t know you like reading.’

Farida did not respond.

At the book market, they were both lost, unlike the shalwar kameez shop because they both did not know their way around books.

‘The Flower with Seven Colours’ Farida told the bookseller.

‘What’s that, Farida Akka?’ Shazia asked her.

‘A Russian children’s book’ Farida replied. She did not tell her that it was her favourite book from her childhood. Or that it was the book her mother read to her every night as she put her to sleep, back in the day when she was still full of hopes and dreams about her daughter’s life.

As the bookseller handed her the book with a colourful flower of seven colours on the cover, Farida felt as if she was handed seven wishes along with it. Unlike Zhenya, the girl in the story who wastes most of her wishes, Farida would not waste her wishes this time.

*

On Monday, Farida was too joyful for a woman who involuntary cries in the car sometimes.

She hummed the melodies of all the songs in Silsila as she made five curries, including the High Commissioner’s favourite dish.

Mohandas had a slight smile drawn across his face as they entered the Shantipath. He had lately started glancing at Farida as she rode in the back seat of the car. Farida returned the smile and looked out the shutter. She felt her cheeks turning to a peach shade, but her eyes looked for Nadeem, a boy with decayed teeth, who danced to an off-beat rhythm selling flags. In a minute he appeared from behind a jeep, smiling at the coins in his hand, and looking around proudly as if he had conquered the world. Farida waved at him and he waved back. But she wasn’t sure if he remembered her face.

She called him and he came running. She wanted to touch his head and pat him on his shoulder for reasons she could not comprehend. On some evenings, she had dreamt of squeezing his puffy cheeks, like they do in the baby cologne commercials on the television.

She had thought about placing a kiss on his forehead and wishing him well. But how could she, in such an unpredictable traffic?

When the boy came to her shutter and smiled, almost as if he remembered her from the previous day, Farida felt her heart pounding faster than the day she first got onto a flight.

She said hello and Nadeem responded showing all his decayed teeth. And suddenly, she heard the vehicles honking. The traffic had started moving. So, she quickly handed him The Flower with Seven Colours and gave him her best smile. Her fingers were trembling, but his were twisted together, covered with dust. There was no time to feel his cheeks or pat him on the shoulder. Let alone place a kiss on his forehead. It was not fair. But she knew quite well about life being unfair too.

*

On the way back to the Residence after the High Commissioner finished his lunch, Farida looked for the boy who sold freedom all over the Shantipath. He had gone missing again.

Farida sighed. But children were intangible. Like the galaxy patterns inside glass balls, they were meant to only to dance in sunlight. So, Farida looked outside the shutter, at the rhythmically swaying tulips on the right side of the road.

A few steps away, behind a massive tree, next to a stack of Indian national flags, was a boy who had missed a button on his shirt, smiling, looking at the pages of The Flower with Seven Colours. Farida felt her eyes tearing up and the tears made her see the boy through a spectrum of seven colours. She was sure he could not read the words, but he was turning the pages. Sometimes the best you can do is turn a page, whether or not you understood the story.

The sunlight was soft that quiet afternoon. As the car drove away from Shantipath, Farida opened the shutter to look at the magnolias dancing by the roadside. Subtle and calming, it smelled like a baby’s cologne outside.

As Mohandas drove her away from the Shantipath, Farida smiled with him and closed her eyes.