English Translation

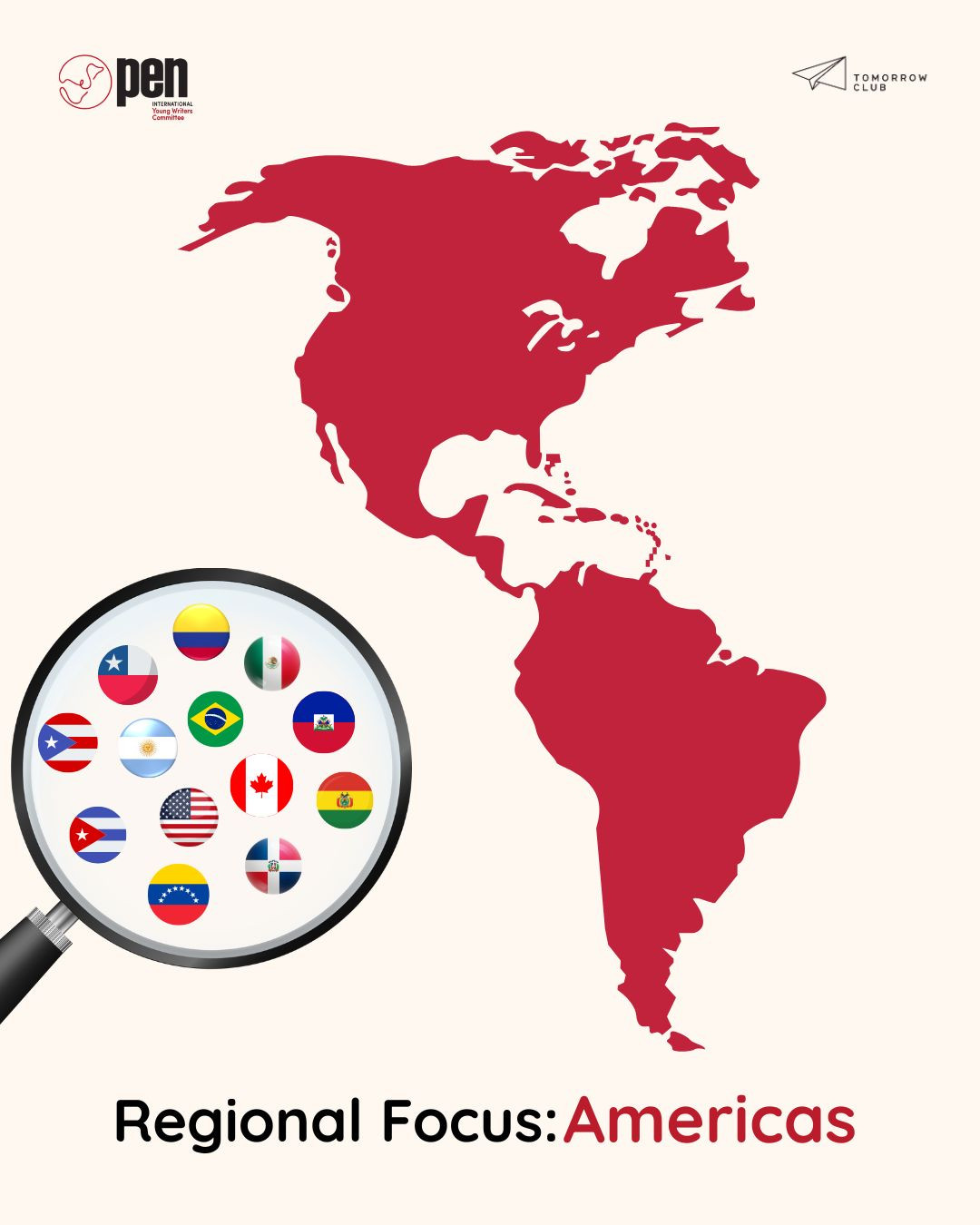

*Listen to the podcast interview in Spanish with Juliana Rozo and other Americas writers, hosted by Regional Editor Carlos Egaña / Entrevista en podcast con Juliana Rozo y otros escritores conducida por el editor regional Carlos Egaña

Todavía tengo el sabor a muerto, me repetía Mariana durante el recorrido. Su casa quedaba en el Siete de Agosto pero no iba hacia allá, no, por ahora estaba quedándose en Niza. El bus cogía toda la Séptima desde Centro Internacional y seguía y seguía y seguía en línea recta. Nuestras nalgas se despegaban del asiento pegajoso cuando frenaba súbito y seguía, seguía, seguía el bus su trayecto que dejaba humo y recogía el cansancio de quien se devuelve a casa después del trabajo. Mariana con su mirada honda apuntando a las vitrinas de Chapinero. Mariana, Mariana, Mariana: su aliento con sabor a muerte empañando el vidrio.

El olor amargo. El sabor gris, su papá: Un cuerpo colgante. Sí que es un malparido me decía y movía su rostro de lado a lado. Esa tarde la había acompañado a su clase de guitarra en Cuatrocuartos. Al salir caminamos desde la Caracas a la Séptima para coger el bus, seguíamos en uniforme de colegio y las faldas soplaban al viento cuando las motos nos pasaban cerca. Ya lo había intentado hace dos meses decía Mariana mientras por los costados de la calle las casas tradicionales de techo triangular nos escoltaban.

Ella y yo, Mariana y yo en el bus sentadas, ella al lado de la ventana y yo al lado de Mariana que no se percató cuando subió una mujer con el pelo negro a la altura de la barbilla con una guitarra colgando del cuello y un gallo agarrado del pescuezo por una cuerda gastada. La voz de la pasajera rasgó el aire, era una voz dulce que aullaba y los ojos de Mariana pegados a la ventana mirando cómo se desaparecían del paisaje las Droguerías La Rebaja, las casas beige, los semáforos y la montaña eterna que nos abrazaba, nos contenía.

El tórax de la cantante subía y bajaba a destiempo de la canción. Para olvidarme de ti voy a cultivar la tierra. Las flores de mi jardín han de ser mis enfermeras. Su cuerpo, su cicatriz en la entreceja se balanceaban con el movimiento del bus. El gallo detrás de ella irradiaba una rigidez mansa. El cuerpo del animal y la cantante como resortes pegados al piso luminoso del bus en la pasarela transversal y en simultáneo los pasajeros querían convertirlos en fantasmas.

Le pregunté si ya había hecho la maleta y mientras su cabeza asentía me preguntaba de vuelta si reconocía de quién era la canción que sonaba. Mariana: su pecho arrítmico como el de la cantante. Solo la había visto moverse con tal intensidad hace seis meses cuando nos besamos en la cocina de su casa mientras le poníamos chips de chocolate y gomitas a los pancakes. También nos besamos en el patio de ropas con tejado de plástico, donde estaban sus instrumentos. Fue con el cable de mi extensión, me dijo también Mariana, con eso lo hizo. La uña golpeteaba las cuerdas, la muñeca rápida como un péndulo, Run run se fue pal norte, empezó a cantar Mariana al unísono con la cantante. Interrumpió la canción y me miró al decir — como nosotras, al norte — y cuando reparó en la presencia del gallo, posó su mano en mi pierna. El gallo atado empezó a aletear adentro afuera arriba abajo. Nadie más lo miraba, solo Mariana y yo. Que si esto que lo otro que la vida es mentira y la muerte es verdad cantaban Mariana y la cantora. Era hora pico, el bus lento y pausado. En el bus: Nuestras piernas pegajosas. El pelo de la que canta, en su frente una gota de sudor. Y las alas del gallo.

No sé cuál es el sabor del muerto o cómo besa quién se ofrece a la muerte. Recuerdo el beso de Mariana. Su labio delgado y la lengua puntiaguda. El frío del dije de la Virgen del Carmen en mi mejilla mientras lamía su clavícula. Ahora solo su mano en mi canto mudo. Su mano encima de la falda a cuadrículas que nos quería arrebatar el viento de Bogotá.

Después de Violeta, me dijo, después de Violeta Parra no hay nada. Apreté su mano, su palma escurrida en sudor. Quería que la fuerza de mi cuerpo le dijera que sí, que tenía razón, y que iba a estar ahí cuando no hubiera nada. Era lo único que le podía dar. Mariana: no sé cómo decirte que sí. Te veo mirar por la ventana intentando olfatear tu saliva para saber a qué sabe un muerto, tu hombro sostiene mi cara y mi pelo liso me nubla la vista. Pasamos el Centro Comercial Santa Bárbara, el día empieza a ser noche y ahí también te puedo decir sí, sí me acuerdo de cuando me pediste el cuadre ahí. Te digo que ya casi me bajo, que te quiero, te quiero Mar y te entrego mi iPod, lo pongo en la marejada de tus palmas. Cuando vuelvas de visitar a tu hermano hablamos y sí, después de Violeta no hay nada. Tus ojos parecen olivas, eso me respondes. Señalas al gallo que te observa mientras aletea y me paro.

ENGLISH

I still have the taste of death in my mouth, Mariana kept saying to me the whole trip. Her house was on Siete de Agosto, but she wasn't going there; no, she was staying at Niza for the time being. The bus traveled the entire length of Seventh Avenue from the International Center and continued straight ahead. Our butts would slide off the sticky seat when he braked suddenly, and the bus continued on its way, trailing smoke and picking up weary passengers going home from work. Mariana, her soulful gaze fixed on the shop windows on Chapinero. Mariana, Mariana, Mariana: her breath, tasting of death and fogging up the window.

The bitter smell. The gray taste, her father: a body, hanging. He's such a bastard, she said to me, shaking her head from side to side. That afternoon, I had gone with her to her guitar lesson at Cuatrocuartos. When we left, we walked from Caracas to Séptima to catch the bus, still wearing our school uniforms, skirts flapping in the wind as motorcycles passed close by us. He tried it before, two months ago, Mariana said, as we passed traditional houses with peaked roofs lining both sides of the street.

She and I, Mariana and I, sitting on the bus, she by the window and I next to Mariana, who didn't notice when a woman with chin-length black hair got on, a guitar hanging from her neck and clutching a rooster by a worn string tied around its throat. The passenger's voice pierced the air, a sweet, howling voice, and Mariana's eyes glued to the window, watching as the Discount Pharmacies, beige houses, traffic lights, and the eternal mountain that embraced us disappeared from the landscape, closing in around us.

The singer's chest rose and fell out of rhythm with the song. To forget you, I will farm the land. The flowers in my garden will be my nurses. Her body and the scar between her eyebrows rocked to and fro with the motion of the bus. The rooster behind her emanated a docile rigidity. The creature's body and the singer were like springs stuck to the bright floor of the bus's center aisle, and at the same time, the passengers wanted to turn them into ghosts.

I asked her if she had packed her suitcase yet, and as she nodded, she asked me again if I knew who wrote the song that was playing. Mariana: Her chest, as arrhythmic as the singer's. I had only seen it move with such intensity six months ago when we kissed in her kitchen while putting chocolate chips and gummies on pancakes. We also kissed in the laundry area with the plastic roof, where her instruments were. It was with my extension cord, Mariana told me, that's what he used to do it. The fingernail was striking the strings, the wrist rapid as a pendulum. Run Run se fue pal norte, Mariana began to sing along with the performer. Run Run went off to the North. She stopped singing momentarily and looked at me, saying—Like us, to the North—and when she noticed the rooster, she put her hand on my leg. The rooster began to flutter back and forth, up and down. No one else was looking at him, only Mariana and I. No matter this or that, life is a lie, and death is true, sang Mariana with the singer. It was rush hour, the bus slow and stopping frequently. On the bus: Our sticky legs. The singer's hair, a droplet of sweat on her forehead. And the wings of the rooster.

I don't know the taste of the dead, or how those who offer themselves to death kiss. I remember Mariana's kiss. Her thin lip and pointy tongue. The chill of her Virgin of Mount Carmel pendant on my cheek as I licked her collarbone. Now, just her hand on my silent song. Her hand on my plaid skirt that the winds of Bogotá wanted to snatch away.

After Violeta, she told me, after Violeta Parra, there's nothing. I squeezed her hand, her palm dripping with sweat. I wanted the strength of my body to let her know that yes, she was right, and I would be there when there was nothing. That was all I could offer her. Mariana: I don't know how to say yes to you. I watch you looking out the window while trying to sniff your saliva to find out what a dead man tastes like, your shoulder supports my face, and my straight hair obscures my view. We pass the Centro Comercial Santa Bárbara, and the day begins to turn into night, and there, I can also tell you yes, yes, I remember when you asked me to go steady with you. I tell you it's almost my stop, I love you, I love you, Mar, and I hand you my iPod, placing it on the stormy seas of your palms. When you get back from visiting your brother, we'll talk. And yes, after Violeta, there's nothing. Your eyes look like olives: Sure, you answer. You point at the rooster, its eyes on you as it flutters, and I stand up.

— Translation from Spanish by D. P. Snyder

BIOGRAPHY

ESP. Juliana Rozo (Bogotá, Colombia) es artista y escritora. Tiene una maestría en Escritura Creativa de la Universidad de Nueva York y formación en historia del arte, filosofía y cine. Su primer libro, Arqueología de un cisne, es un ensayo personal y poético que explora la relación entre la belleza, el trauma y la violencia utilizando la figura del cisne como símbolo central; fue publicado por Smol Books en 2024 y en 2025 se publicó la edición bilingüe inglés-español con Sundial House Press. Ha sido docente en distintas universidades de Bogotá y Nueva York. Es Tauro, ascendente Virgo y Luna en Sagitario.

ENG. Juliana Rozo (Bogotá, Colombia) is an artist and writer. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University and has academic training in art history, philosophy, and film. Her first book, Arqueología de un cisne, is a personal and poetic essay that explores the relationship between beauty, trauma, and violence, using the figure of the swan as a central symbol. It was published by Smol Books in 2024, and, in 2025, a bilingual English–Spanish edition was released by Sundial House Press. She has taught at various universities in Bogotá and New York. She is a Taurus, with Virgo rising and the moon in Sagittarius.