English Translation

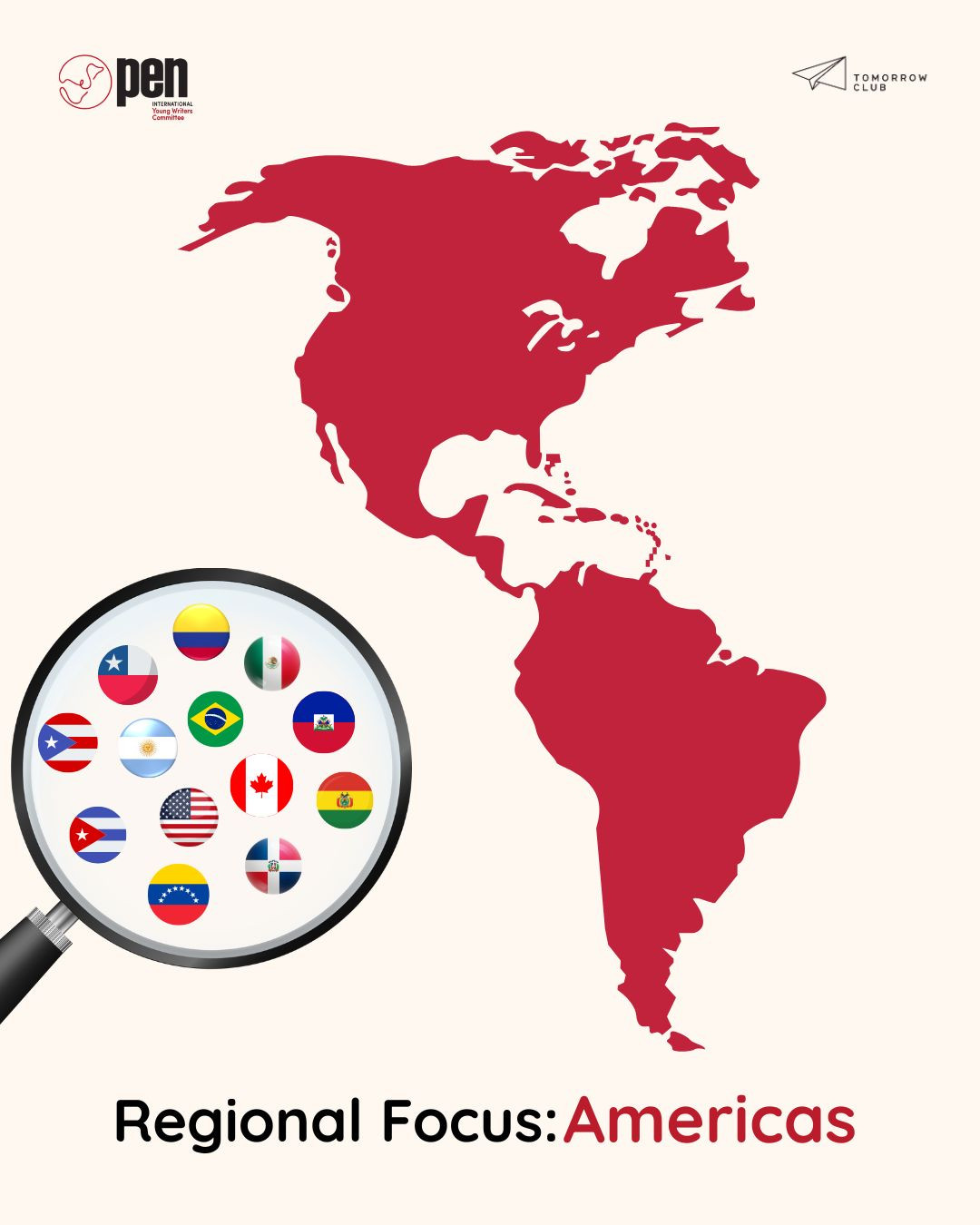

-Podcast interview hosted by Regional Editor Carlos Egaña with Louise Belmonte and other Americas writers / Entrevista en podcast conducida por el editor regional Carlos Egaña con Louise Belmonte y otros escritores de las Américas

Em nenhum momento dos últimos dias, que não foram nada fáceis ou calmos, Catarina imaginou que essa trilha, precisamente, é o que mais lhe causaria arrepios. Estou te esperando; ela disse; Minha casa é fácil de achar: paredes verdes, sem grades, sem número; Eu nem acredito que vou te ver. Caminha devagar, equilibrando o peso da mochila nos ombros. O chão está escorregadio pela chuva da madrugada. Ao lado, vê pequenas casas de madeira, outras de alvenaria, algumas pintadas de cores vivas, outras descascadas pela maresia. É um dia cinza, e a ilha toda parece desbotada também, como se as imagens da água cristalina que tinha visto no Google tivessem sido mergulhadas num tanque sujo. Um cheiro de mato molhado sobe das raízes expostas. Um homem passa puxando um carrinho de mão carregado de caixas. Catarina abaixa a cabeça, tentando não demonstrar seu deslocamento, o seu, como eles dizem? Agringamento.

Está cansada. Vê uma pedra em forma de banco e decide parar um instante. Abre o Instagram no celular. A primeira imagem que surge é um vídeo de um pôr do sol em Tel Aviv, o sol se pondo atrás do oceano, e a voz de uma menina falando: sinto muito, eu ainda amo viver aqui, olha isso, só pode ser inveja, é por isso que eles fazem isso, esse é o melhor lugar do mundo. Ela silencia o perfil e fecha o Instagram. No peito, um nó cego e sem palavras, enquanto imagens dos últimos dias atravessam o Atlântico: primeiro, as bases americanas bombardeadas no Golfo. Depois, a declaração oficial e em menos de dois dias Israel ataca Teerã, e o Hezbollah responde no norte. Na televisão, explosões como se fossem jogos de luzes sobre a cidade. O Hamas também intensificou seus ataques e parecia que o mundo inteiro tinha decidido se destruir de uma vez. Foi quando a Rússia anunciou apoio ao Irã e a China se calou no Conselho de Segurança que seus pais decidiram voltar. Voltar para um país que ela nunca tinha ido, mas que, ainda assim, o verbo mais adequado era esse: voltar. Trancar a matrícula na universidade, por um semestre no máximo, a mãe prometeu, pensa nisso como um intercambio cultural, tentou o pai, mas o que resistia era o sentimento de raiva e vergonha em estar indo embora quando finalmente algo assim passa a acontecer nesse país. Naquele país.

A verdade é que bastou eles pousarem para ela sentir o alívio: é que começaram os primeiros apagões nos Estados Unidos. Primeiro em Boston, depois Nova York. Na semana seguinte, bancos fora do ar. Suas amigas passaram dias sem conseguir comprar comida. O governo decretou leis de emergência. Recrutamento obrigatório até os quarenta anos, restrição de viagens, cortes em programas sociais. E nas ruas, os protestos. Judeus ortodoxos agredidos na calçada. Muçulmanos tendo suas casas pichadas com ameaças de morte que, com certeza, já estavam sendo efetuadas em lugares onde as câmeras ainda não alcançavam, ou não queriam alcançar. Enquanto isso, ela descobria novos tipos de frutas. Olhava para outros gringos que ocupavam o calçadão de Ipanema com uma mistura de casa e constrangimento. Conheceu tios e primos dos quais só tinha ouvido falar e que, só por existir, a fizeram se sentir pálida e enrijecida. Tia Amira lhe olhou de cima abaixo e disse: e uma cor, não vai bem não? Como se o corpo dela pudesse simplesmente ser melhor. Ela tentou argumentar sobre a falta de companhia para ir à praia o que, para a tia pareceu uma piada, mas logo depois ela ficou muito séria e disse; E você nunca foi para a praia sozinha? Pois vá, é uma terapia. E foi na praia, olhando para toda aquela gente com caixas de som, biquinis coloridos, óleos de bronzear que faziam a pele brilhar, picolés, chá mate e biscoito que ela viu: uma mulher jovem cuidando de um bebê. Ela ficou ali, sentada na areia, observando. Observou tanto que a cena pareceu ir entrando na pele, nos poros, na saúde. Começou a criar uma imagem que, depois se deu conta, não correspondia a imaginação e sim à criança. Ela na praia. Uma mulher que não era sua. O mar sorrindo e deixando de sorrir, sorrindo e deixando de sorrir. Chegou em casa e perguntou para a mãe que, sem expressar grandes emoções, respondeu; ah sim, você deve estar lembrando da Zuleide. Zuleide, Zuzu e Dimdim. Sinais de trânsito apagados reacendem todos de uma vez e ela lembra do rosto e do cheiro e da voz dessa mulher de nome Zuleide que a criou até os cinco anos, enquanto seus pais trabalhavam alucinados na agência. Zuleide que lhe ensinava a cantar em português, que lhe levava para ver a lua na quinta avenida, que cheirava a cigarro e inventava histórias antes de dormir. Onde ela está agora? Foi rápido de descobrir, apesar da resistência da mãe: Tia Amira tinha o número de todo mundo. E tinha. E Catarina escreveu, com as palavras torpes que tinha, no português raso que acessava, dizendo que sim era ela, que sim estava no Brasil, que sim queria vê-la, caso Zuleide quisesse. Para sua surpresa, o telefone tocou logo depois sinalizando uma mensagem; Muitas vezes eu quis fazer isso, mas achava que tinha que vir de você. A partir desse momento, uma adrenalina desconhecida percorreu seus ossos e as notícias sobre a guerra pareciam tão distantes quanto um dia lhe pareceu a palavra Brasil.

E agora ela estava ali, naquela trilha chegando à casa verde, sem grades, sem número. Teve de pegar um barco, Zuleide morava numa ilha próxima ao Rio de Janeiro. Se sentiu animada no caminho, não sabia porque fazia isso mas sabia que fazia, sabia que algo nela não deixava de se escrever, e que havia algo também naquelas palavras: sem grades, sem número, que a puxavam e tornavam a subida do morro menos tortuosa. Foi então que enxergou. A casa. Uma vontade de chorar baixinho. Seguiu caminhando. Alcançou a porta branca, que tinha um chaveiro de coelho pendurado no lugar do olho mágico. Achou graça, mas estava nervosa. Tocou a campainha e Zuleide abriu a porta e usava um vestido longo e estampado e a abraçou repetindo duas palavras que começavam com s e soavam como um ritmo, como um mantra ou como uma música que ela sabia, eram duas palavras simples: que sonho, que susto, Zuleide dizia e repetia, que sonho, que susto, que sonho, que susto. Então ela afastou Catarina do peito e a olhou no fundo dos olhos para revelar o terceiro e final s da tríade: e que saudade, ela disse por fim, que saudade gigante.

As duas se sentaram à mesa posta por Zuleide: café, pão francês, suco de laranja, pão de queijo, bolo, queijo, presunto, um banquete que fez Catarina se sentir especial. Mas antes dos olhos encontrarem a fartura, primeiro encontraram as paredes, todas pintadas com listras, e o teto com borboletas de tecido penduradas, era tanta informação e ao mesmo tempo nada era gratuito, e foi então que Catarina se lembrou das palavras de Zuleide, todas tão exatas, e foi então que se deu conta, meu deus, ela pensou: eu fui criada por uma poeta.

Você entende o que eu digo? Zuleide lhe perguntou e ela fez que sim, disse que entendia bem, só falar era um pouco mais difícil; Ah com o tempo você pega rapidinho e tudo isso volta... Você lembra de como a gente escutava Bruno e Marrone?; e ela canta com a voz rouca, enquanto mexe na xícara de café; Seu moço eu não sou delinquente, eu sou um cara carente, eu dormi na praçaaaa, pensando nelaaaaa. A voz de Zuleide cantando evoca mais um algo e essas memórias do corpo são coisas com as quais não se conta e para as quais não existe preparo e Zuleide a olha e pega na sua mão e diz; você sabe, não sabe? Que eu sou um baú da sua infância. Catarina não sabe o que responder e toma um gole do café enquanto ela continua; E me conta, o que você estuda? Aposto que é super ocupada, né?

Eu curso jornalismo, quer dizer, cursava né... Agora tive que parar...

Ah sim, desde pequena você escrevia...Você, assim, não sabia ler, não era alfabetizada. Eu me lembro, você sentou no sofá e tinha um livro que... Tinha que ler aquele livro. Direto. Tão direto, tão direto. Que você sentou naquele sofá e começou a abrir, começou a ler. Aí depois mudou a página, leu, mudou pra outra, leu. Mas você... Era como se você estivesse realmente lendo. Porque você já estava tão acostumada de eu ler aquilo que tinha decorado o que tinha em cada página, sabe? Essa cena, todo mundo ficou assim, olhando e ficou chocado com aquilo, sabe? Não tá muito forte, né? O café.

Não, tá ótimo, tá perfeito.

Mesmo se não estivesse perfeito, estaria perfeito né? Viu? Mas aí foi... Aí eu falei... Aí eu fiquei ligando sua história, agora, do jornalismo. Com aquilo lá atrás. Com esse episódiozinho, sabe? Muito... É. A vida é muito assim. E os seus pais?

Catarina levanta os olhos e encontra os olhos de Zuleide. As duas se encaram e na suspensão da pergunta existem muitas outras que pairam no ar. Ela sente seu o estômago endurecer, e a saliva ficar salgada, talvez tenha sido algo que comeu, ela olha para a mesa farta, ela sente medo, ela olha novamente nos olhos de Zuleide e é quando o telefone da casa toca e Zuleide corre para atender e literalmente corre, pula do banco de madeira e num instante está com o telefone móvel colado no ouvido, uma máquina que Catarina nem sabia que ainda existia, e ela parece afoita, pergunta primeiro se a pessoa está bem, a pessoa parece dizer sim, pergunta onde ela está e chora umas lágrimas pequenas, diz que imaginou um monte de horrores mas não esse, e então diz; Vem embora minha filha, vem pra casa e nessa hora a pessoa que está do outro lado da linha fala um pouco mais alto e Catarina consegue escutar; E a gente nadou nadou pra morrer na praia, mãe?!, e aquela saliva salgada demais, o estômago duro, contraindo e adormecendo, uma vontade de vomitar e bolo e pão de queijo e guaraná e a filha de Zuleide, que nunca tinha passado pela cabeça de Catarina, e é então que ela se dá conta que nunca tinha passado na sua cabeça que Zuleide tivesse uma filha, que Zuleide tivesse uma vida, e então novas memórias, Zuleide falando com seu pai de dentro do carro, a barriga de Zuzu, mais saliente, o braço do pai apoiado no vidro e por que? Ela olha para o lado e num porta-retrato a foto de Zuleide com uma adolescente, não parece fazer tanto, a foto, meu deus, será que a filha adolescente está em outro país e tem que dizer a palavra medo numa língua que não é sua?

Ela desliga o telefone e caminha devagar até Catarina. Meu Deus, você tá branca. Baixou a pressão, será? O calor faz isso mesmo com a gente.. E ela passa as mãos nos olhos vermelhos, fingindo que não tinha choro nenhum ali. Sobre o que estávamos falando mesmo?, ela pergunta e Catarina mente, diz que estavam prestes a falar dela. Não, mas eu não tenho muito pra contar, porque... É... Eu... A minha vida é mais a trabalho, trabalho, trabalho, trabalho. Por exemplo... Hoje eu cuido de duas crianças. Um menino de sete, que eu fui lá quando ele nasceu. E agora tem a irmãzinha dele. Tem dois anos. São uma graça as crianças, sabe? E... Eu acho assim que eles... Ele... O pai das crianças, ele é irmão do ex-marido da esposa do Ricardo, sabe? Catarina não sabe quem é, mas faz que sim com a cabeça.

Você me dá licença, Dimdim, que eu vou ligar aqui a novela um instante, pra deixar no mudo mesmo, sabe? Zuleide se levanta e a palavra Dimdim atinge Catarina nas pernas que parecem nunca mais serem capazes de se levantar e a novela ainda não começou, no lugar dela o jornal mudo, mostrando imagens do conflito, os olhos de Zuleide chupados na tela, Nova Iorque aturdida e silenciosa e você tem uma filha, Zu? Ela escuta sua própria boca dizer e Zuleide se vira, os olhos ainda vermelhos; Tenho, a Tamara. Tá com dezesseis anos hoje. Zuleide olha novamente para a televisão e segue dizendo; Tá lá agora, vivendo com uma amiga minha, da época que eu cuidava de você. Tamara queria ter uma vida diferente e eu deixei ela tentar... Meu deus, que a proteja. Mas Catarina está só meio escutando porque faz as contas do tempo e olha novamente para a foto de Tamara e sente algo forte na garganta: um medo, uma pergunta, uma certeza que ainda não tem nome e pulsa e repara: sua foto bem pequena logo ali ao lado e são parecidas as duas, ela e Tamara, tem algo de similar, ela e Tamara, e nesse momento Zuleide a olha e diz; Você sabe… Quando eu soube que você tava aqui no Brasil, eu pensei que Deus tava me devolvendo uma filha.

ENGLISH

Not once over the last few days, which have been anything but easy or calm, did Catarina imagine that this very path would be the one to give her goosebumps. I’ve been waiting for you; she said; My house is easy to find: green walls, no gate, no number; I can't believe I’m about to see you. She walks slowly, balancing the weight of her backpack on her shoulders. The ground is slippery from the early morning rain. On one side, she sees small wooden houses, others of stone, some painted in bright colors, others peeling from the sea breeze. The day is grey, and the entire island looks faded as well, as if the images of the crystal-clear water she'd seen on Google had been dunked into a dirty pond. The smell of wet scrub rose from the exposed roots. A man walking by pulling a cart loaded with boxes. Catarina lowers her head, trying not to show how out of place she was…what is it they say?…a perfect ‘gringa’.

She's tired. Seeing a rock shaped like a bench, she decides to stop for a moment. She opens Instagram on her phone. The first image that appears is a video of the sun setting behind the ocean in Tel Aviv, a girl’s voice saying: I'm sorry, I still love living here, look at this, it can only be envy, that's why they do this, this is the best place in the world. She silences the profile and closes Instagram. In her chest a blind and speechless knot, as images of the last few days cross the Atlantic: first, the American bases bombed in the Gulf. Then, the official statement, and just two days later Israel attacks Tehran, and Hezbollah responds in the north. On TV, explosions shower lights over the city. Hamas also intensifies its attacks, and it seems as if the whole world had decided to destroy itself for good. That was when Russia announced its support to Iran and China remained silent at the Security Council that her parents decided to return. Return to a country she’d never been to; even so, the right verb was 'return'. Just a semester off, her mother promised, think of it as a cultural exchange, argued her father, but she felt angry and ashamed of leaving when finally something like this was happening in this country. In that country.

But the truth is that as soon as they landed, she felt relieved: that's when the first blackouts hit the United States. First in Boston, then New York. The following week, the banks went offline. Her friends couldn`t buy food for days. The government imposed martial law. Compulsory recruitment for those up to the age forty, travel restrictions, social program cuts. And in the streets, the protests. Orthodox Jews attacked on the sidewalks. Death threats spray painted on Muslims homes which were surely being carried out in places where there were no cameras, nor would there be. Meanwhile, she discovered new types of fruit. She looked at other 'gringos' strolling along the Rio de Janeiro beachfront sidewalk with mixed feelings of homesickness and embarrassment. She met uncles, aunts and cousins she had only heard of and who, just by existing, made her feel pale and stiff. Aunt Amira looked her up and down and said: you look like you need a tan! As if her body could simply be better. She defended herself by saying she didn't have anyone to go to the beach with, which seemed like a joke to her aunt, who then took hold of herself and said; you've never been to the beach alone? Well then, you should: it's like therapy. And it was at the beach, surrounded by all those people with loudspeakers, the colorful bikinis, the tanning oils that made their skin glow, the popsicles, the mate tea, the biscuits, that she saw a young woman taking care of a baby. She sat there, on the sand, watching. She watched so intently that the scene seemed to seep into her skin, her pores, her health. She began creating an image that, she later realized, wasn’t in her head, but in her inner child. On the beach. A woman who wasn’t hers. The smile of the sea that came and went, came and went. She got home and asked her mother who, without raising an eyebrow, replied; yeah, you must be thinking of Zuleide. Zuleide, Zuzu and Dimdim. Traffic lights light up all at once, and she remembers the face, the smell, the voice of this woman named Zuleide who took care of her until she was five, while her parents worked all day at the agency. Zuleide who taught her to sing in Portuguese, who took her to see the moon on Fifth Avenue, who smelled of cigarettes, who made up stories at bedtime. Where was she now? She quickly found out, despite her mother's reluctance: Aunt Amira had everyone's number. And she did. And Catarina wrote her, in her own clumsy words, in her shallow Portuguese, saying yes it was her, that yes she was in Brazil, that yes she wanted to see her, if Zuleide also wanted to, that is. To her surprise, the phone rang shortly after that, signaling a message; I had always wanted to do this, but I thought it had to come from you. At that moment, an unfamiliar adrenaline rush ran through her body, and the news of the war seemed as distant as the word Brazil had once did.

And now there she was, on the path leading to the green house, with no gate, no number. She had to take a boat, Zuleide lived on an island near Rio de Janeiro. She felt excited on the way, didn't know why she was doing this but knew she was, that something in her would not stop writing itself, and that there was something in these words: no fence, no number, that pushed her forward and made the climb up the hill less tortuous. That's when she saw it. The house. She wants to cry quietly. She kept walking. She reached the white door, and there was a rabbit keychain hanging where the peephole was. She found it funny, but she was nervous. She rang the bell and Zuleide answered the door wearing a long, patterned dress and hugged her, repeating two words that began with an s and that had a certain rhythm, like a mantra or a song she knew, two simple words that started with an s: what a sight, what a surprise, Zuleide said and repeated, what a sight, what a surprise, what a sight, what a surprise. Then she held Catarina at an arm’s length, looked deep into her eyes to reveal the third and final word: ‘saudade’, to say she truly missed her…’saudade’.

They sat down at the table Zuleide had set: coffee, French bread, orange juice, pão de queijo, cheese, ham, a feast that made Catarina feel special. But before her eyes met the feast, she noticed the surroundings, the walls all painted with stripes, the cloth butterflies hanging from the ceiling. It was so overwhelming, but it was all there for a reason, and that’s when Catarina remembered Zuleide's words, all so precise, and then she realized; my God, I was raised by a poet.

You understand what I'm saying? Zuleide asked her, and she nodded, saying she understood well, but talking proved more difficult; Ah, in time you'll understand, and it will all come back... Do you remember how we used to listen to Bruno and Marrone? And she sang in a hoarse voice, stirring her coffee: Seu moço eu não sou delinquente, eu sou um cara carente, eu dormi na praçaaaa, pensando nelaaaaa. Zuleide's singing evokes something else, and these body memories can be so unexpected, which one cannot prepare for, and Zuleide looks at her and takes her hand and says; you know, don't you… I am a trunk of your childhood. Catarina doesn't know what to say, sips her coffee, and then she continues; And tell me, what are you studying? I bet you're super busy, right?

I study journalism, or rather, I used to... but I had to stop...

Oh yes, you've been writing ever since you were little... You, like, didn't know how to read, you hadn't learned yet. I remember you sitting on the sofa and there was a book that... that you had to read. Right then. Right then and there. You sat on that sofa, opened it, and started to read. Then you turned the page, read it, turned another, read it. But you... it was as if you were actually reading. Because you were so used to me reading it that you had memorized each page… That scene, everyone was, like, watching and surprised, you know? It's not too strong, is it? The coffee.

No, it's great, it's perfect.

Even if it weren't perfect, it would be anyway, right? See? But then... Then I said... Then I started connecting the dots, you taking journalism. With what happened that day. With that little episode, you know? Very... yeah. Life’s a lot like that. And your parents?

Catarina looks up and meets Zuleide's gaze. The two look at each other and the suspended question leaves others floating in the air. She feels her stomach turn, a salty taste in her mouth, perhaps from something she ate, looks at the lavishly set table, feels scared, looks again into Zuleide's eyes, when the phone rings, and Zuleide rushes to answer it, literally flying off the wooden chair, and in an instant the cordless phone is glued to her ear, a device Catarina didn't even know still existed, she seemed uneasy, first asking if the person was okay, the person apparently says yes, asks where the person is, tiny tears run down her cheeks, she says that she imagined all kinds of horrible things but not this, and then says; Come on over, honey, come on home, then the person on the other end of the line speaks a little louder, and Catarina can hear what she is saying; And all that was for nothing, mom?!, and that salty taste, the knotted stomach, tight and numb, wanting to throw up the cake, the pao de queijo, the guaraná, and Zuleide's daughter, it had never crossed Catarina's mind, and that's when she realized that she had never imagined that Zuleide had a daughter, that Zuleide had a life, and then new memories, Zuleide talking to her father from inside the car, Zuzu's belly, more prominent, her father's arm leaning on the window, and why? She looks to one side and sees a framed photo of Zuleide with a teenager, it doesn't seem to be that long ago, could that, oh my God, could that be her teenage daughter in another country, who now has to pronounce the word fear in a language that is not her own?

She hangs up and slowly walks over to Catarina. My God, you look pale. Did your blood pressure drop? The heat does that to us... And she rubs her red eyes, pretending she wasn't crying. What were we talking about again? she asked, and Catarina lied, saying they were about to talk about her. No, there`s not much to say, because... yeah... I... My life is mostly work, work, work, work. For example... Now I take care of two children. A seven-year-old boy, from the moment he was born. And now his little sister. She's two. They´re so cute...? And... I think that they... He... The children's father is Ricardo's wife's ex-husband's brother, you know? Catarina doesn't know who he is, but nods as if she did.

Excuse me, Dimdim, I'm going to turn on the soap opera here for a moment, the sound will be off, ok? Zuleide stands up and the word Dimdim hits Catarina in the legs which seem to never be able to stand up again and the soap opera hasn't started yet, instead the silent news, showing images of the conflict, Zuleide's eyes glued to the screen, New York stunned and silent and you have a daughter, Zu? She hears the words coming out of her own mouth and Zuleide turns around, her eyes still red; I do, Tamara. She’s sixteen today. Zuleide looks back at the TV and continues; She's there now, living with a friend of mine, from when I took care of you. Tamara wanted a different life, and I let her try... May God protect her. But Catarina is only half listening because she is calculating how long ago this was and shifts her gaze back at Tamara's photo and feels a knot in her throat: a dread, a question, a certainty that still has no name and pulses and notices: her tiny picture right there next to Tamara’s and they are so alike, she and Tamara, there is something similar about them, she and Tamara, when Zuleide looks at her and says; You know... When I found out you were here in Brazil, I thought God was bringing me back a daughter.

— Translation from Brazilian Portuguese by David Haxton Jr.

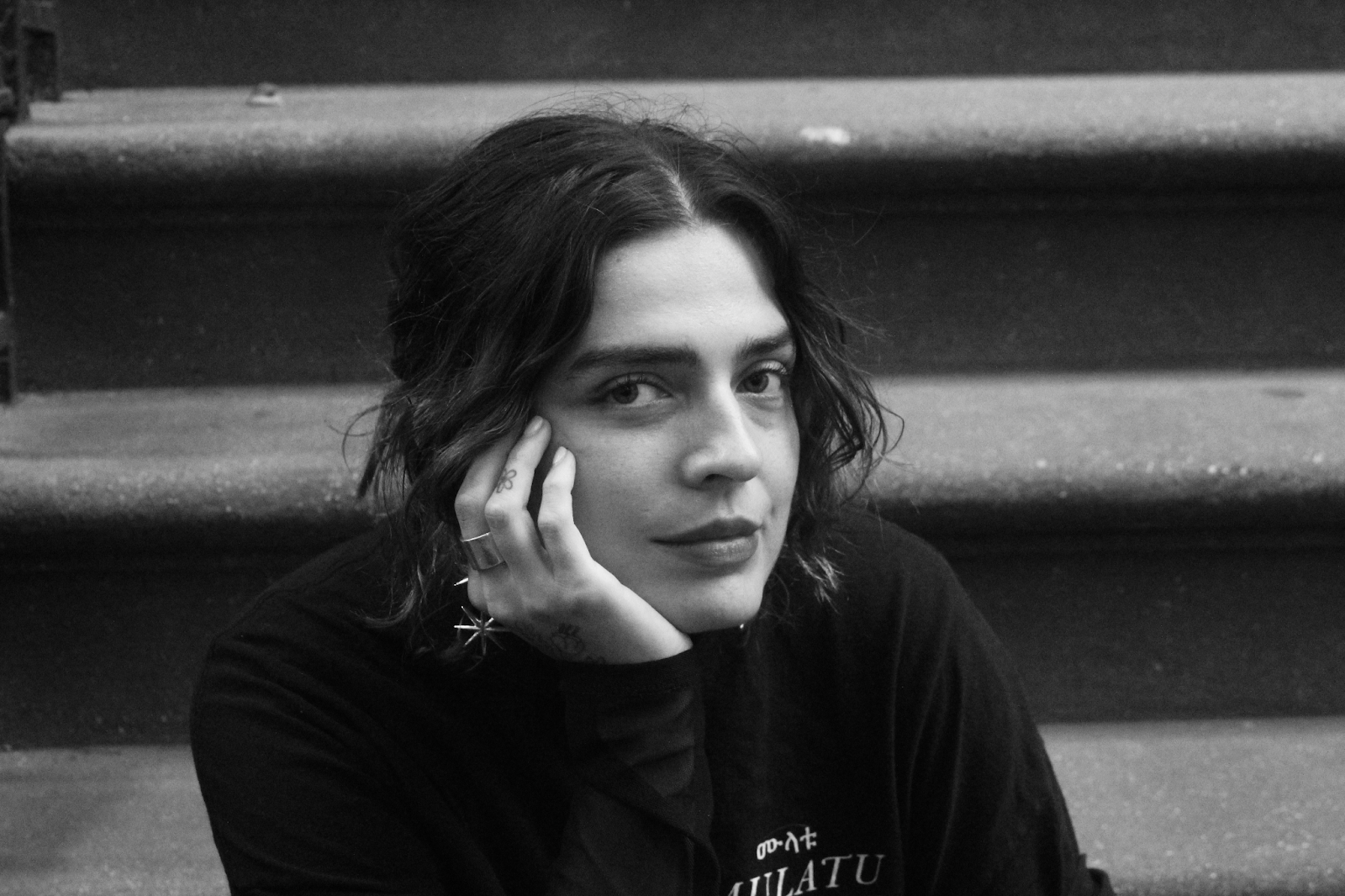

BIOGRAPHY

PT. Louise Belmonte (Brasil, 1995) se formou em Cinema pelo Instituto Armando Alvares Penteado, em São Paulo, Brasil. Desde então, tem trabalhado com literatura, teatro e cinema. No cinema, é diretora e roteirista do curta-metragem La Mer, exibido no Festival de Cinema de Ouro Preto. No teatro, é autora da peça Fuga, que estreou em São Paulo em julho de 2025, no Sesc Belenzinho. Louise é produtora, coordenadora e educadora no Instituto Frestas, escola nômade que já percorreu os 26 estados do Brasil, difundindo conhecimento, arte e cultura. Em 2022, publicou seu primeiro romance, Primeira Pele, e em 2023, seu primeiro livro de poesia, Incessantemente Não Saber, ambos pela Editora Quelônio. Atualmente, está em formação em psicanálise no Centro de Estudos Psicanalíticos de São Paulo e cursa o MFA em Escritura Creativa en Español na Universidade de Nova York, onde escreve seu segundo romance

ENG. Louise Belmonte (Brasil, 1995) graduated in Film from the Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP) in São Paulo, Brazil. Since then, she has worked in literature, theater, and film. In cinema, she is the director and screenwriter of the short film La Mer, which was screened at the Ouro Preto Film Festival. In theater, she is the author of the play Fuga, which premiered in São Paulo in July 2025 at Sesc Belenzinho. Louise is a producer, coordinator, and educator at Instituto Frestas, a nomadic school that has traveled through all 26 states of Brazil, spreading knowledge, art, and culture. In 2022, she published her first novel, Primeira Pele, and in 2023, her first poetry collection, Incessantemente Não Saber, both with Editora Quelônio. She is currently training in psychoanalysis at the Center for Psychoanalytic Studies in São Paulo and is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing in Spanish at New York University, where she is writing her second novel.