Traditions of My Homeland

Every second of November

as the azacuanes take flight

my mother would lay flowers

somewhere in El Salvador

she said this is

how you honor

those who have no grave.

*

Every year

she left her flowers

in a different place

*

To her, the whole country

was one vast memorial.

Junín

*Originally published on Lavoz De Los Barrios

The first time I read in front of 100 people

I ran 4 blocks from the Junín station

with J de Juli

with J de Juan Solá

who was also reading that night

and I was opening for them

like those new bands

who take advantage of the moment

their moment, far from Buenos Aires

much further from El Salvador

from that bar in the city of Antiguo

where I read for the first time, in front of 8 people,

that afternoon, my friends preferred to go play soccer

my mother was the one who applauded the most

I fell in love with someone

an unrequited love

one of those loves where only poems remain

written in the silence of rejection

in the intimacy of papers

like that erotic poem I read one night

where I could barely read the letters

conditioned by the effects of a vodka

that we called vodka out of pure trust in the label

that night when someone applauded

he asked for the poem with enthusiasm

and I thought did he really like it?

It was one of those loves that were not slow this time,

although I also learned slowness in detachment

because love never knows how to end on time, it is always too soon,

it is always too late,

like my arrival at the cycle in Junín, where I made the typical joke about my accent

to break the ice, a joke to make a difference,

to steal with a difference, to enhance that silence

in which one believes the story

that poetry saves, that poetry illuminates,

the only poetry that illuminates is that which burns,

said that rapper, who sang about anarchy

and now asks for more cops on the block, because watch out!

Be careful not to be so radical and end up going around

like the ones the bus takes to Junín,

the humid pampas,

in that city that has more prisons than it deserves,

to which a few months later I went with her,

the one who spoke of emotions,

the one who taught me to speak of emotions

and left the whole neighborhood

with the nostalgia of a fishing village

when one night, she went out the door,

she left her key hanging on the wall,

in those days I learned that it wasn't poetry,

nor heartbreak, nor absent friends,

nor cheap vodka

Neither long distances nor anarchist rap

because hell is not other people,

hell is carried within oneself,

one is saved by genuine applause from the friends who remain,

in the 15 minutes of contemplation that one steals from the day

when waking up each morning,

betting that life will continue to be worthwhile.

About the Author

César Saravia (El Salvador, 1989) is a poet and journalist whose work moves between memory, territory, and the intimate landscapes of language. He has made Argentina his home since 2015.

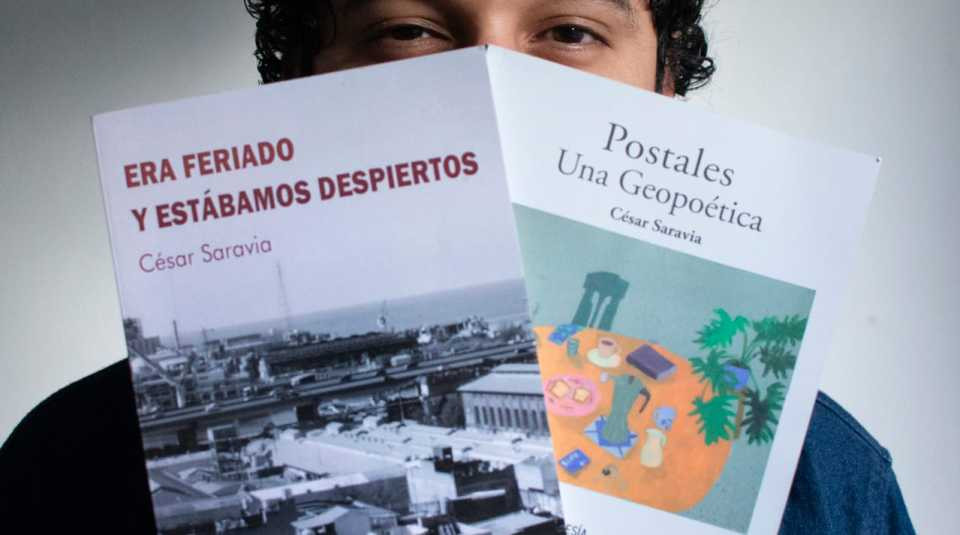

His first book, Era Feriado y Estábamos Despiertos (Editorial Colibrí, 2018), explored the quiet rituals of everyday life. In 2024, he published Postales. Una Geopoética awarded the 17th National Poetry Prize “Adolfo Bioy Casares,” organized by the City of Las Flores.

Saravia is a member of PEN Argentina, part of the editorial collective Marcha Noticias, and the creator of Modo Verso, a space for poetry and conversation.