Dear Theo,

You may have heard or read about the significant freeze in government funding for both domestic and foreign aid, a policy shift initiated by the Trump administration. Specifically, efforts related to inclusion, gender rights, and democracy have been impacted. Unfortunately, one of our major grants has been affected by this change. We’ve been notified by our funder that the grant has been delayed, not cut. As a result, we will need to delay your start date. At this time, we are still awaiting further updates from our funders and don’t yet have a new start date to share.

My boss' email with the subject line ‘Urgent: your employment’ arrives while I am in transit through Changi airport. In the days leading up to my relocation, my father pestered me about how NGO work was for stupid hippies: they were good-for-nothing expats who posed as gods in southeast Asia with their Australian passports, only to return home with nothing to show for. Meanwhile, according to him, their sensible friends did down-to-earth stable jobs, saved up money, married 'the right' people, had 'the right' kinds of families... My father would constantly burst into my room with lines like ‘at the end, people only care if you have a good job and income’ and ‘no one cares if you can read Vietnamese novels.’

If only he knew that the NGO work specifically related to Vietnam, the birth country he has been trying to disown. Not only did the Fall of Saigon mark the seizure of his family’s wealth and property but his family remained insulated in the minority Chinese community which the rest of Vietnamese society viewed as clannish and suspicious.

The irony is that I never opposed a conventional life but that my father was a large part of the reason I could never root myself in Sydney. He had already been pestering me about my job prospects at the conclusion of my PhD. I was the only one in my extended family who had opted out of the doctor/healthcare career path.

At the same time, I was a failed academic: I had not produced enough peer-reviewed articles, conference presentations or networking links in my four years of study. The time spent poring over the history and philosophy of psychology also meant that I was lacking in the soft skills and slickness favoured among industry professionals.

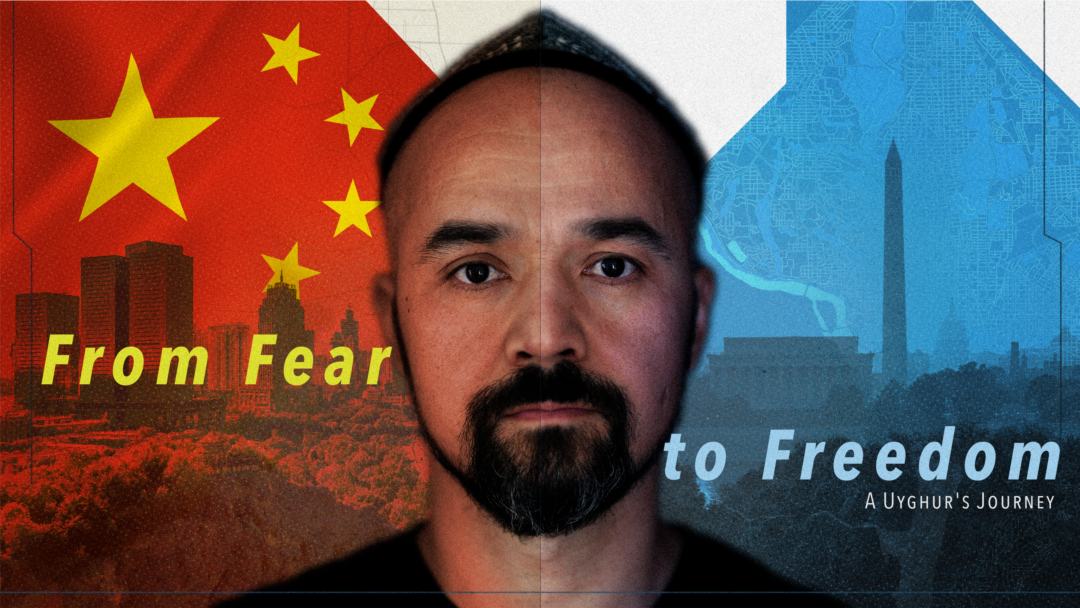

I was only selected to work at an exiled Vietnamese NGO due to a peculiar confluence of skills, most of which I am just passable at: I speak Vietnamese (although Hanoians point out how my accent is ‘contaminated’), casually debated political topics through angry op-eds, can use Excel (after my doctoral supervisor coached me through a shame-induced meltdown), and am content with frugal living (although even a very modest life can take a significant amount of money in this economy). Other than that, becoming a human rights defender or activist had never crossed my mind.

The first accommodation in Bangkok was a ground floor unit in Bang Kapi. A flyscreen covered the strip of window along the back but evidently, I was still connected to nature because a gecko crawling along the mesh ended up exploring the edge of the ceiling inside. There was no sink or hot water, although I had worked out how to use the provided bucket as a sink that could be washed out using the shower and bidet. The weather was hot enough to shower in cold water just fine.

I lay in a star shape on the mattress. The fan tacked to the wall dried sweat to my face. There is a popular superstition that you will die if you sleep with the fan on. Forty-five-degree days without air-conditioning in Australian Christmases made me ignore that.

My mother replied to my job panic in our Viber chat: 'just come back home.' If returning home did not entail daily verbal abuse, I am not sure I would have left at all. I might have followed the prudent advice of academic and even other mentors from the NGO sector. They advised I be patient and apply for more mainstream jobs in Australia. That would be a better next step then an obscure post with a Vietnamese organisation.

However, the choices were between relocating to a foreign country that I had never visited and an indefinite period of familial contempt and failure as I pressed the submit button on Seek.com for months on end. Perhaps if I had just waited, one of my hundreds of job applications would have returned with positive jobs. Indeed, a market research organisation emailed stating that a project had opened and that my research skills and former industry experience would be appreciated. But I had already set my mind upon moving before the work’s projected start date.

With the foreign aid crisis, I wonder if my fate is to return to 'the lucky country' and disappear as a second-class human in my local communities. Even when I tried pretending to want a stable healthcare career and family, it never stuck: I would end up wondering about the origins of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual or some other conceptual side quest. I never sought exciting romantic partners and was content dating a Johnny Tran or Henry Chong from one of Sydney's academically selective boys' schools. In fact, I thought the idea of marrying a high school sweetheart would make my love life simpler. But those boys seemed to like the skinnier, prettier Asian Australian girls in my school who got straight As. Furthermore, the aspiration of marrying young disappeared when a mixture of observing friends’ relationship breakdowns and an addiction to podcasts about psychopaths and narcissists showed that locking in a marriage was no guarantee of future emotional happiness.

Surely though, there needed to be some middle ground between the ‘white picket fence, nuclear family’ facade and being stranded and unemployed on one’s first day in a foreign country. This move to Bangkok was not my first foray into Vietnam’s civil society sphere. My first NGO supervisor and I argued about the sudden decision to discontinue my work with them. Our argument ended with him saying, ‘you should seriously reconsider a career in activism. It’s high risk and low pay. If you’re so panicked about this situation, I’m very concerned.’

He must have thought this insult would crush my professional ambitions. But he was correct to doubt my devotion to activism or Vietnam. It made no sense for me to stand by the South Vietnamese flag whose regime died long before my birth. But for a long time, I assumed my sudden and unexpected acquisition of the Vietnamese language obligated me to accept patriotic baggage. In reality, the linguistic connection was a residue of my writerly disposition rather than politics.

After all, my first love was literature. An old copy of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis sits in an open luggage bag. The spine is ripped halfway down the middle. Though I had already read it several times, I could not help but purchase at my old university’s spring sale: Franz Kafka was my high school hero. His novels shattered the moral binaries and superficial standards of success. Among a cohort of perfectionistic, skinny Asian Australian girls, I delighted in an intellectual world outside dot point-checking Higher School Certificate syllabuses.

Perhaps family members drew assumptions about my dumbness from my disinterest in study. In retrospect, I was likely normal for a primary school-aged child but unacceptable compared to my cousins who endured hours-long tutoring sessions with joy. I resigned myself to being a failure. Even after trying to sit down in front of a textbook, my father would only become angrier than before and yell when he saw me. ‘See?! That donkey only does what she's told after being pushed 100 times!'

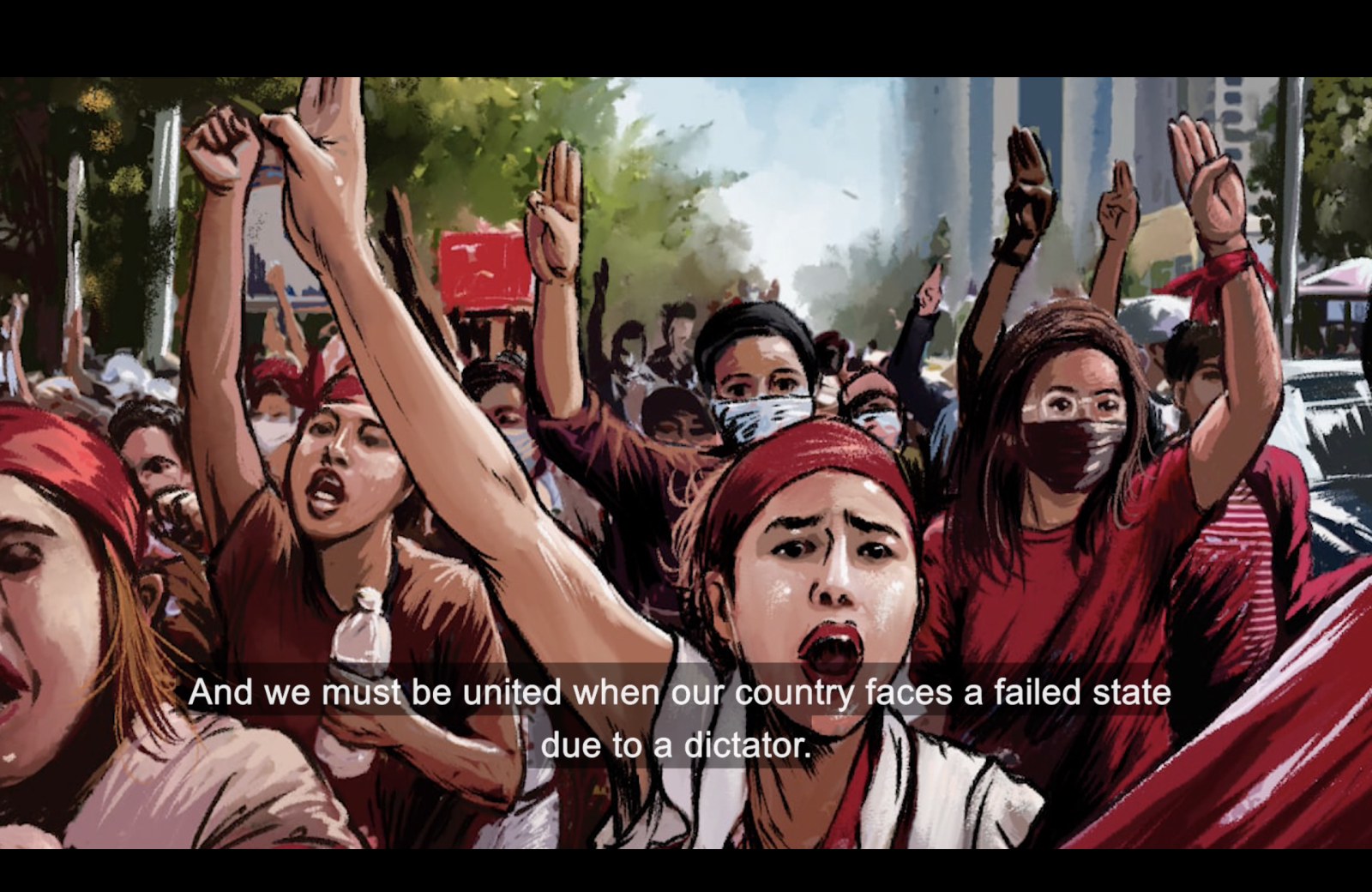

Regardless of whether my behaviour was ‘normal’, it was enough for me to seek validation elsewhere. My newfound Vietnamese fluency brought me under the wing of Bác Hùng, an elder in the Vietnamese community, who began inviting me to community events so I could ‘practise speaking Vietnamese’ and ‘learn more about my roots.’ At the time, I did not realise that these events were run by Việt Tân, an exiled pro-democracy party which the Vietnamese government has listed as a terrorist organisation since 2016. Even now, Việt Tân’s political activities and history seem mysterious, partly because of my own limited Vietnamese fluency and lacking knowledge about Vietnamese society and the War.

What I did know was that I was the only person under 30 at these events, save for a few bored children who would play outside until it was dinner time. The adults there gushed about how good my Vietnamese was. With a CD of Tuấn Vũ’s songs playing during the drive back home, Bác Hùng said he was so proud when people commented on my interest in Vietnam’s politics and language: born in Australia, they said, but speaks just like a girl from Saigon and cares about her quê mẹ! I was no longer just a mediocre frump from western Sydney, never taken seriously as an intellectual in seminar groups dominated by inner-city and northern suburbs dwellers, the ugliest and least impressive child in the extended family.

Now, spitting toothpaste into a bucket-turned-sink at a cheap Airbnb, I wonder: would I have followed Bác Hùng if I had been more than an ugly, stupid child scrounging for scraps of kindness? If I had just kept my personal interests aside and appealed to my family’s ambitions, could I be working at a GP practice (or Big 5 firm, if we're staying in the non-healthcare direction), dating a good Asian Australian boy, on the path to earning enough savings to raise a family and provide for aging parents in the future?

In theory, operating and holding citizenship outside a totalitarian regime should make activism safer. Certainly, I can appreciate that my Vietnam-based colleagues face the risk of being followed, tracked, and the Công An seizing their devices every day.

But the level of secrecy can still be high and draining even if only from a convenience perspective. Many of my friends outside the NGO world have not dealt with jobs that require hiding one's face and real name from colleagues. What if people in my personal life are friends with Vietnamese international students, some of whom could be spies for the Vietnamese Communist Party?

The fan dries out my eyes as I list alternate income streams: freelance writing/editing, remote research assistance, interview analysis and transcription. My bosses will likely replace me – the ‘she’ll do’ candidate - with someone better: I imagine this to be a Vietnamese student at an international school (so they would be a perfectly balanced bilingual), always knowing what to research before a meeting without being asked, always articulate when answering in either Vietnamese or English, never missing chat messages… When that perfect replacement comes, my bosses will remove me under the guise of ‘further funding cuts’ to avoid addressing the real issue: that I was never good enough to begin with.

This submission is an edited combination of entries 1 and 2 from the Substack series 'Theodore Pham's Diary: Bangkok.' https://tphamdiary.substack.com/