I. The Question I Cannot Escape

What would my mother say if she could see the world her children inherited? She died before the prisons and camps swallowed whole neighborhoods of our homeland. She died before families like mine were scattered to distant continents. She died before the Uyghur language—the lullabies she whispered, the prayers she recited, the jokes she told—was forbidden in schools and punished in official settings. The title of my memoir comes from this hard-to-believe yet instinctive realization: Good That Mother Was Gone Before She Could Witness This. My work is not only to write a book. My work is to resist disappearance. For Uyghurs, the simplest truths—our language, our prayers, our being as a sovereign ethnic group—are being erased. A memoir becomes more than memory; it becomes survival.

II. Childhood in Kashgar

I was born in Kashgar in 1979, the fourth of five children. For the Chinese state, Kashgar was the edge of the world it had conquered—closer to Samarkand and Kabul than to Beijing, the capital that claimed to rule us. My earliest memories are full of contrasts: the brilliance of apricot blossoms against Andijan-style walls and the shadow of Mao’s statue towering above mosques older than Mao’s empire. On Thursdays, I followed my grandmother to the ancestral cemeteries to honor the dead. On Sundays, I followed my uncle Anwar to the bazaar. The Sunday Bazaar was a universe in itself—tents of silk, carpets piled high, pyramids of melons, the clang of clay pots, the neighing of horses. There, at thirteen, I became a shopkeeper. It happened suddenly. My uncle Anwar died, and with him the fragile balance of our family collapsed. Someone had to take over his stall. School ended for me that day. Numbers became my textbooks; bargaining became my grammar lessons. I no longer memorized answers to exams; I memorized the faces of regular customers. My teens were exchanged for adult life. At night, when the bazaar closed, I returned home with tired feet and pockets filled with notes. My grandmother looked at me with pride and sorrow mixed together—pride that I kept my uncle’s business afloat, sorrow that a child’s education had been traded for business. Years later, I realized exile began for me not when I left Kashgar, but when I left the classroom. I was exiled from childhood itself.

III. Learning to Speak

Life has a way of teaching us in hidden classrooms. In the bazaar I learned to calculate quickly, to read faces, to survive in a world where every transaction mattered. And I learned languages—English among them. English arrived as a whisper of possibility, an improbable door out of confinement. By eighteen, I had clawed my way back into formal schooling. I carried both determination and defiance: determination forged by years in the bazaar, defiance that my life would not be confined to its narrow alleys. English became my obsession. I stayed up late rewriting, repeating words, imitating sounds from cassette tapes and radio signals. I copied speeches from books, not knowing that one day I would stand on a national stage delivering one myself.

IV. Becoming Visible

In 2004, I traveled to Beijing for the national English-speech competition broadcast on China Central Television. It was my first time in the capital. For a boy from Kashgar, it felt like stepping onto another planet. I spoke about dreams and the possibilities education might open in a life like mine. The lights were blinding, the cameras intimidating, but my voice did not shake. I was the first Uyghur student to reach that level of the competition. When the applause came, I felt the pride of representing my people. For a moment, I believed visibility meant acceptance. But visibility in China is double-edged: to be seen is to be marked. After the competition, I was invited to “drink tea” with the plain-clothes police. Their questions were gentle but sharp—Who had helped me? What did I really believe? Was I trustworthy? They reminded me that success was permitted only if loyalty was proven. That day I learned that visibility is both a stage and a target.

V. Building Atlan

In 2006, I founded Atlan Language Center in Urumqi. What began as small classes grew into one of the region’s largest private schools—over 100 staff and 10,000 annual students. We taught English not only as a language but as a window into the world, a key that might open futures. For Uyghur youth, Atlan became more than a school. It was a refuge, a place where dreams were not yet criminal. I watched students arrive timid and leave with voices strong enough to imagine lives beyond surveillance. But every achievement was shadowed by fear. Authorities visited often. They monitored curricula. They reminded me that too much Uyghur pride, too much independence, was dangerous. Still, I held on. By 2017, the contradictions of my life had reached their peak. While the unimaginable was happening to those I cared about most, the authorities named me a “National Model Entrepreneur.” That May, I was brought to Beijing to meet the Chinese vice president in the Great Hall of the People. Outwardly I was celebrated as a symbol of success; inwardly I was already planning my escape. Meanwhile, 2017 was becoming the year of silence. More and more friends and students disappeared. Scholars and mentors who had once guided me with wisdom were taken one by one. The city itself transformed—checkpoints every few blocks, cameras in every corner, QR codes on doors, armed police marching with helmets, guns, and batons. Colleagues were herded away before my eyes and never seen again. It was then I made the hardest decision of my life: to leave.

VI. Exile

I arrived in the United States with my wife and our toddler daughter in late 2017. I carried no wealth—only memory. Weeks later, I heard that Atlan had been shut down. My staff and colleagues were arrested. The school I had built over a decade was erased in a single order. I sat in a small apartment in Arlington, Virginia, staring at the walls, feeling the weight of guilt. I had escaped, but at what cost? Exile is not only distance. It is the silence when you call home and no one answers. It is the fear that your words might endanger those you love. It is waking at night to echoes of voices you may never hear again.

VII. Why I Write

In exile, I became a journalist. At Voice of America I reported daily in English and Chinese, producing more than 300 stories about Uyghurs. I believed in journalism’s power to illuminate. When Beijing found out, they arrested at least a dozen former colleagues from Atlan. Regardless of their innocence, the regime sentenced many to five- to ten-year prison terms. Even as I wrote, I knew news reports were fleeting. They informed, but they did not preserve. That is why I began writing my memoir. A memoir is slower than news, but deeper. It does not only tell what happened; it tells how it felt, how it broke and remade us, how it lives inside our bodies. I write because statistics cannot capture the smell of bread in Kashgar’s alleys or the sound of a grandmother whispering a prayer. I write because official documents cannot explain the guilt of a man forced to abandon his homeland or the pride of a young teacher watching his students find their voices. I write because silence is what power demands—and words are what the silenced require.

VIII. The Work Itself

My memoir, Good That Mother Was Gone Before She Could Witness This: A Uyghur Son’s Search for Survival and Voice,is structured in four parts and twenty-four chapters: Part I — Exile and Arrival: the journey to the U.S., asylum, the first years of separation. Part II — Coming of Age in Occupied Homeland: childhood in Kashgar, adolescence, the rise as student-teacher and entrepreneur. Part III — Repression, Complicity, and Global Indifference: mass detentions, silence, journalism in exile. Part IV — Propaganda’s Global Triumph: how the state manipulates memory—how some exiles resist, while others remain silent or are even turned into instruments of its narrative.

The work blends personal testimony with broader reflection on authoritarianism, memory, and identity. It is at once deeply individual and urgently collective.

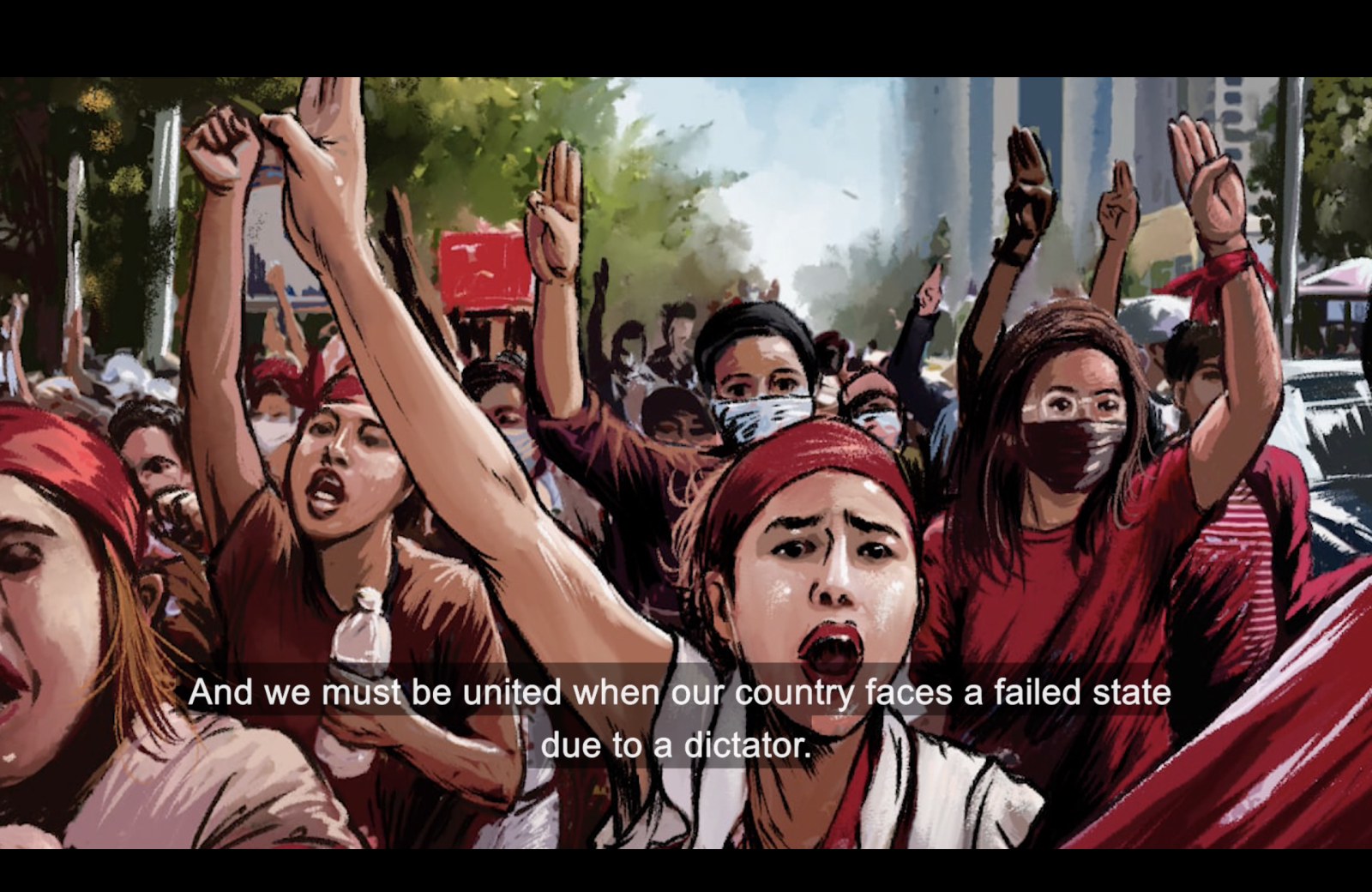

IX. To Young Peers

This work is not only for me. It is for young peers—Uyghur or not—who live with the weight of displacement, who wonder whether their voices matter. I want to tell them: survival is not only about staying alive. It is about refusing silence. It is about preserving language, memory, and dignity even when stripped of land and home. Literature gives us this power. It allows us to speak across time, across borders, across the walls of prisons and the silence of graves.

X. Closing

Sometimes I return, in dreams, to Kashgar’s Sunday Bazaar. I see the colors of cloth, the rhythm of bargaining, the faces of people who are now gone. I hear my mother calling me home for dinner. She did not live to witness the world of camps and cameras. For that, I am relieved. But I live to witness it—and I live to resist it. And so I write. Even in exile, even in silence, I will not be erased. We will not be erased.