English Translation

Podcast interview hosted by Regional Editor Carlos Egaña / Entrevista en podcast conducida por el editor regional Carlos Egaña

Estas reflexiones están motivadas por sucesos recientes. A nadie le está permitido evadirse enteramente de su propio tiempo. Podría aquí parafrasear a Silvina Ocampo y decir que no puedo ser único ni distinto. Sin embargo, como ocurre muchas veces, en lo cotidiano podemos encontrar ecos de lo universal.

La identidad nacional y sus diversas ramificaciones han caracterizado a las grandes cuestiones de los siglos XIX y XX. La afirmación de una identidad, su defensa y sobre todo su imposición, han creado más de una tensión y sangrientos desencuentros.

En América Latina y el Caribe, el tema siempre está vigente. Abordado por las izquierdas y derechas, por republicanos y tiranos, por pensadores y hombres de a pie, el tema de la Patria ha dado literatura, pintura, música y muerte.

Temerosos y orgullosos

Los estados latinoamericanos y caribeños han tenido en común la sensación de sentirse vulnerables y a merced de las potencias. En el siglo XIX había que liberarse del yugo de los grandes imperios coloniales y evitar volverse títeres de otros.

En el siglo XX la amenaza era más terrible que la nuclear y los hombres y las mujeres se sentían en la mira de la Unión Soviética y de los Estados Unidos.

Hoy, en el instante en que escribo estas líneas, el temor es ser solamente una factoría o mercado para productos chinos o estadounidenses.

Pero al mismo tiempo, casi esquizofrénicamente, estos estados que tanto han discurrido sobre el temor, han esgrimido, en mayor o menor medida, una jactancia arielista. En algunos casos, como el argentino, se ha creado una verdadera idea, un tanto ególatra, de que las potencias buscan aplastar al único rival que puede hacerles frente.

Una civilización barbárica

Es curioso que los estados latinoamericanos y caribeños han replicado como algo natural una serie de dicotomías muy particulares que podríamos resumir, a grandes rasgos, en la lucha entre la Civilización y la Barbarie. En pleno siglo XXI, todos nos damos cuenta (o deberíamos) de que los defensores de la Civilización no eran tan civilizados, ni los bárbaros tan barbáricos. Ni que los excesos de unos justifican el exceso de los otros.

Imposible no pensar en esta cuestión que, de alguna forma, gravita entre nosotros y que muta solo superficialmente. En esencia es un mismo fantasma que solo cambia de sábana.

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento se puede llevar los laureles de ser el creador de la corriente que pensó la cuestión. También de ser uno de los impulsores más geniales de la idea de que lo mejor era eliminar, no siempre civilizadamente, al contrario. En el campo de la literatura, su magnífico Facundo (1845) fue el árbol frondoso que dio frutos como la magistral Doña Bárbara (1929) de Rómulo Gallegos (1884-1969) o unos muy curiosos como Yo, el supremo (1974), de Augusto Roa Bastos (1917-2005), y los libros que forman el subgénero conocido como “Novela del dictador” y de aquel otro subgénero, la “Novela del caudillo”, en la que se inscribe La muerte de Artemio Cruz (1962) de Carlos Fuentes. Y no es casual que solo mencione hombres: en América Latina, machismo y literatura muchas veces van de la mano.

El conflicto maniqueo se ha mantenido latente, más o menos, con estas actualizaciones: el campo contra la ciudad, la capital portuaria europeizante contra las ciudades criollas de provincias, el pueblo contra la oligarquía, los aliados de los marxistas contra los aliados de los yanquis, los nacionalistas contra los vendepatrias… y así una larga lista de nombres y caracterizaciones que suelen esconder el tufillo del oportunismo político y de intereses non-sanctos. Y así se cumple la sentencia que Elena Garro escribió en Los recuerdos del provernir porvenir (1963): “Una generación sucede a la otra, y cada una repite los actos de la anterior”.

La Patria en peligro

Siempre, igual, brilla la misma cuestión: la disputa por la patria. El leitmotiv que impulsa estos discursos nacionalistas parte de la idea de que una porción de la población está guiada por creencias equivocadas con la que ha sido timada por un grupo de poder que busca beneficiar intereses espurios de alguna potencia allende sus fronteras.

En esta disputa por la patria, no puede faltar el discurso xenófobo. Países que, como la Argentina, abrían sus puertas a la inmigración, hoy estigmatizan a los extranjeros. Claro que el fenómeno de los siglos XIX y XX que expulsaba oleadas de Europa era visto en muchos estados americanos como la posibilidad de “mejorar la raza”. Recibir españoles, franceses, italianos, alemanes, ingleses, irlandeses, idealmente blancos, representaba el anhelo de las grandes ciudades de nuestro continente para reemplazar al elemento nativo (los indígenas y los criollos mestizos). Y también para reemplazar a los primeros “transplantados”: los esclavos africanos y su molesta descendencia. Porque gran ciudad americana que se precie de tal, tiene sus barrios donde predomina una minoría poblacional que poco y nada tiene que ver con las características físicas, culturales y económicas del resto del país. Y de esos barrios señoriales y coquetos, en general, han salido gobernantes que no se parecen a sus gobernados.

Hay que aclarar que pareciera que a los estados americanos (y aquí hay que sumar a nuestro poderoso hermano del norte) lo que les molesta no son los extranjeros en sí. Lo que les molesta son los pobres. No vienen a mi memoria discursos contra profesionales finlandeses o suecos. Pero si podemos tirar para el techo discursos y expresiones contra “bolitas”, “paraguas”, “cholos”, “mojados”, “perucas”, “frijoleros”, “changos”. Hoy la medalla al pueblo despreciable se lo llevan los venezolanos que huyen de la tiranía chavista/madurista. Incluso en aquellos países que se declaran abiertamente contra el régimen.

No es una novedad decir que este fenómeno, hoy por hoy, se ha vuelto global. Ni ser un signo de los tiempos lo hace excusable. Cada país pareciera tener a un grupo de pobres a los que despreciar. España se siente invadida por “sudacas” y “moros”. Francia e Italia por “bougnoules” y “marocchini”. Y en cada país surge el temor de la pérdida de la identidad nacional.

Al enemigo no se lo desprecia abiertamente por pobre, pues eso no lo permite la corrección política. Entonces se buscan otros reproches: “Nos quieren cambiar nuestro estilo de vida”, “nos quitan los trabajos”, “vienen a robar”, “son terroristas”, “se comen a los perros”. Incluso en porciones de la población “bien pensante” y que ha impuesto el progresismo, más como una moda burguesa, con puño de hierro. “Es difícil –escribe Edwidge Danticat en Crear en peligro. El trabajo del artista migrante (2010)– […] no preguntarnos por qué el mundo desarrollado necesita tan desesperadamente distanciarse de nosotros”.

Grietas en el muro

Sin dudas que el mundo se está compartimentado más y más. Cuando no bastan las fronteras de los cartógrafos, se levantan muros y alambradas. El auge de las nuevas derechas autoritarias en el mundo y que, particularmente en Latinoamérica, se imponen a los progresismos autoritarios de izquierda, fomentan el estado de desconfianza entre los pueblos.

Sin embargo, no todo está perdido. Cuanto más oscuro es el ambiente, con más fuerza brillan las pequeñas luces que se cuelan por las grietas en las murallas que, pretenciosas y ofensivas, aíslan a los de adentro y a los de afuera.

El continente americano nos ha dado más de un mensaje en las últimas décadas sobre las posibilidades de la hermandad humana. Voy a mencionar solo a tres, por una cuestión caprichosa y de afinidad.

Americanos para el mundo

Hay un chiste que escuché recientemente que dice que América ha dado al mundo 4000 variedades de papas. Pero que desde 2013, ha dado 4002. Se refiere, este chiste de salón, a los papas Francisco y León XIV.

Hombres de la fe, líderes de la Iglesia Católica, nos han invitado con su ejemplo a tender puentes y a no construir muros.

Francisco eligió vivir como inmigrante en el Vaticano. Tras su elección como Sumo Pontífice en 2013, decidió no cambiar su ciudadanía y seguir siendo representado por sus documentos nacionales argentinos. Y esto no responde a esas demostraciones patrioteras en las que solemos caer por estas tierras. Ese gesto, de ser un migrante, como sus abuelos, no puede leerse en forma aislada del resto de su pontificado, que incluyó en sus primeros días una misa en Lampedusa, usando como altar los restos de una barcaza naufragada en la que habían perdido su vida varias personas anónimas provenientes de África que trataban de llegar a una Europa opulenta, indiferente y despreciativa.

Por su parte, León XIV nos ha regalado un gesto muy concreto antes de su llegada a la Cátedra del apóstol Pedro. Más de dos décadas como misionero en el Perú, al religioso agustino oriundo de Chicago, le dejaron, además de un perfecto español, un pasaporte. Porque optar por otra ciudadanía no es novedad. Pero optar por la de un país con las típicas problemáticas latinoamericanas como las del Perú, siendo poseedor del pasaporte más poderoso y codiciado, sí que lo es. Robert Prevost eligió abrasarse con las personas que vivían realidades de las periferias existenciales. Podemos decir que así, de alguna forma, se volvió un verdadero americano. Y no solamente un “American”, ese término, un poco vanidoso y que ciertamente suena insolente, con que aún se identifican los estadounidenses.

Una cuestión del individuo

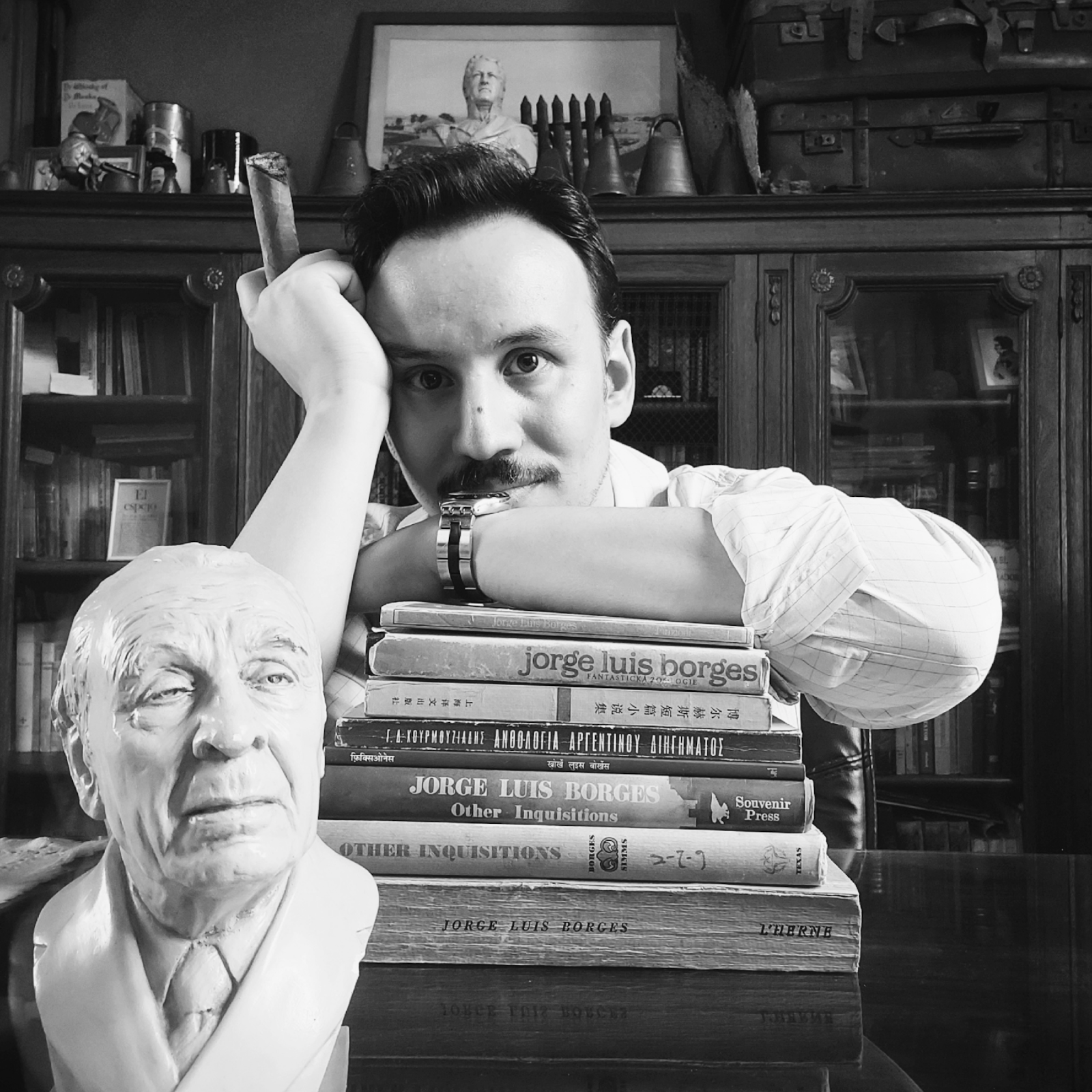

En tercer lugar, no puedo dejar de mencionar a este escritor; estoy en mi biblioteca, rodeado por sus libros y retratos: Jorge Luis Borges, quien no solo creyó en el poder de la literatura como instrumento de la felicidad humana.

El autor de cuentos como El Aleph (1945) o Las ruinas circulares (1940) le atribuyó a la literatura ser un vehículo de la imaginación que podía modificar la memoria y, por lo tanto, el poder de cambiar el pasado, el presente y el futuro.

La obra de Borges también plantea, así, la paradoja de que se escribe la Historia desde la imposibilidad material de acceder a la Verdad. Por lo tanto los libros de historia y las biografías, no son más que la ficción del que las escribe. Obviamente, esa imposibilidad histórica también convierte en ficción a las memorias y autobiografías. Descreer de la posibilidad de escribir la historia nos invita a cuestionar la imposición de mitos nacionales y patrióticos. En definitiva, a liberarnos de las pesadas cadenas de la identidad.

Pero la patria y la identidad no son malas, reflexiona Borges. Tampoco son necesariamente buenas. Lo malo sería creer que una identidad nacional es superior o mejor a otra y que un individuo, por la fortuita casualidad de nacer de un lado u otro de una línea imaginaria, “tan caras a los cartógrafos”, es portador de una identidad mejor que la de otros. En todo caso, el fervor patriótico también es una elección individual. Borges expresó siempre un sentimiento argentino, pero arraigado en lo universal. No por nada enumeraba más de una patria y reconocía como tales a Buenos Aires, Texas y Ginebra.

Borges, genio literario y maestro de la palabra, pero con aciertos y errores como cualquier otro individuo, retomó una cuestión que, en Argentina, ya había planteado Leopoldo Lugones: la conquista y evangelización llevada a cabo por España nos hacía herederos de Roma, Grecia e Israel. Por lo tanto, ciudadanos del mundo. Hombres y mujeres que podían optar por una nacionalidad o por otra, por un mito patrio establecido o inventarse uno nuevo, pero que nunca podían dejar de estar hermanados por algo irrenunciable: la humanidad.

La Luna no está tan lejos

¿Quién puede presumir hoy en día de ser puramente argentino, guatemalteco o brasileño? ¿Qué pueblo en el mundo no se ha visto modificado por conquistas territoriales o movimientos poblacionales? Los humanos y la cultura se han movido siempre y de forma ininterrumpida. ¿Acaso un inglés de hoy no sufrió cambios y tiene la misma identidad y cultura que uno de la era victoriana, o uno de la República de Cromwell u otro de los tiempos de Guillermo de Normandía? ¿Y un colombiano? ¿No hay diferencias con los de los tiempos de Bolívar? ¿Y con aquellos que hace diecinueve milenios legaron pictogramas rupestres en los abrigos rocosos de Chiribiquete?

Borges en el poema homónimo que cierra su último libro Los conjurados (1985), que, de alguna forma, es el punto final de su obra y simbólicamente de su vida, escribió que un grupo de personas “de diversas estirpes, que profesan diversas religiones y que hablan en diversos idiomas” estaban conspirando y habían tomado “la extraña resolución de ser razonables”. Esto, entendía el escritor, era “olvidar sus diferencias y acentuar afinidades”. “Mañana -escribió- serán todo el planeta. Acaso lo que digo no es verdadero, ojalá sea profético”.

Hoy, parece aún más extraña la resolución de ser razonables. Pero también parecía extraño, imposible, irrealizable llegar a la Luna.

ENGLISH

These reflections are inspired by recent events. Nobody has a license to entirely escape from their own time. I might paraphrase Silvina Ocampo here and remark that I cannot be either unique or different. Nevertheless, as so often happens, we can encounter in the quotidian echoes of the universal.

National identity and its various manifestations have characterized the defining issues of the 19th and 20th centuries. The assertion, defense, and, above all, imposition of identity have given rise to more than a few tensions and bloody conflicts. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the issue is always current. Addressed by leftists and right-wingers, republicans and tyrants, thinkers and ordinary people, the theme of the homeland has given rise to literature, painting, music, and death.

Fearful and Prideful

The Latin American and Caribbean states have shared the sensation of feeling vulnerable and at the mercy of great powers. In the 19th century, it was crucial to break free from the yoke of the great colonial empires and avoid becoming puppets of others. In the 20th century, the threat was more terrifying than nuclear war, and men and women felt they were in the crosshairs of the Soviet Union and the United States.

Today, at the very moment I am writing these lines, the fear is becoming merely a factory of or a market for China and the United States.

But at the same time, almost schizophrenically, these states that have so loudly expressed their fears have, to a greater or lesser extent, displayed an Arielist pretentiousness. In some cases, such as Argentina's, a genuine and somewhat egotistical idea has been conceived that the major powers seek to crush the only rival that can stand up to them.

A Barbaric Civilization

Curiously, Latin American and Caribbean countries have repeated a succession of very specific dichotomies that we can generally summarize as the conflict between Civilization and Barbarism. In the middle of the 21st century, we all realize (or we should realize) that the defenders of Civilization were not so civilized, nor the barbarians so barbaric. Nor did the excesses of one justify the excesses of the other.

One cannot help but ponder this question that hangs over us in some way and that mutates only superficially. In essence, it is the same ghost in a different sheet.

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento can claim the distinction of being the founder of the school of thought on this issue. He was also one of the most brilliant promoters of the idea that the best course of action was to eliminate, and not always in a civilized manner, the adversary. In the field of literature, his magnificent Facundo was the leafy tree that bore fruit such as the masterful Doña Bárbara by Rómulo Gallegos and some very peculiar ones such as Yo, el supremo by Augusto Roa Bastos, and the books that are part of the subgenres known as the “dictator novel” and “the caudillo (or autocrat) novel”, which includes The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes. And it is no coincidence that I name only men: in Latin America, machismo and literature frequently go hand in hand.

The Manichean conflict has more or less remained dormant with these updates: the country versus the city, the Europeanizing port capital versus the Criollos (the descendants of Spaniards born in the Americas), cities versus the provinces, the people versus the oligarchy, the allies of the Marxists versus the allies of the Yankees, the nationalists versus the traitors....and so on in a long list of names and labels that generally exist to hide the slight stench of political opportunism and crooked interests. And thus, the sentence that Elena Garro wrote in Los recuerdos del porvenir is fulfilled: “One generation follows upon the other, and each repeats the deeds of the one before."

The Homeland in Peril

The same theme always shines through: the struggle for the homeland. The leitmotif that drives these nationalist discourses is based on the notion that a portion of the population is guided by erroneous beliefs by which it has been duped by an elite that seeks to benefit from the spurious interests of some superpower beyond its borders.

In this struggle for the homeland, the xenophobic discourse must not be lacking. Countries like Argentina, which once opened their doors to immigration, now stigmatize foreigners. Naturally, the extraordinary events of the 19th and 20th centuries that expelled waves of migrants from Europe were viewed in many American states as an opportunity to “improve the race." Welcoming Spaniards, French, Italians, Germans, English, Irish— ideally all of them white—represented the aspiration of the great cities of our continent to replace the native element, that is, the Indigenous and mestizo Criollos. And also, to replace the first “transplants”: the African slaves and their troublesome offspring. Because every self-respecting American city has its neighborhoods with a predominant minority population that has little or nothing to do with the physical, cultural, or economic conditions of the rest of the country. And, as a rule, from the stately and charming neighborhoods, governors who do not resemble the governed have emerged.

It should be clarified that it seems that American nations (and here we must include our powerful sibling to the north) are not bothered by foreigners per se. What bothers them is poor people. No polemics against Finnish or Swedish professionals spring to mind. But we can throw around speeches and derogatory terms against “bolitas” (Bolivian immigrants), “paraguas” (Paraguayan immigrants), “cholos” (mestizo people), “mojados” (wetbacks), “perucas” (Peruvian immigrants), “frijoleros” (beaners), and “changos” (Haitian immigrants). Today, the prize for the most contemptible national group goes to Venezuelans fleeing the Chávez-Maduro tyranny. Even in those countries that openly declare their opposition to the regime.

It is no secret that this phenomenon has now gone global. Being a sign of the times doesn't justify it. Every country seems to have its group of poor people to despise. Spain feels it is invaded by “sudacas” (South Americans) and “moros” (North Africans). France and Italy by “bougnoules” and “marocchini” (Blacks and Muslims). And in every country, there is the fear of losing the national identity.

The enemy is not openly despised for being poor since political correctness does not permit this. Thus, they look for other things to criticize: “They want to change our way of life”, “they take our jobs”, “they come here to steal from us”, “they're terrorists”, “they eat dogs." Even among segments of the “right-thinking” population that have imposed progressivism with an iron fist, primarily as a bourgeois fashion. “It's hard," writes Edwidge Danticat in Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work (2010), "[…] not to wonder why the developed world so desperately needs to distance itself from us.”

Cracks in the Wall

There is no doubt that the world is becoming increasingly divided. When mapmakers' borders are not enough, walls and fences spring up. The rise of new authoritarian right-wing movements around the world, particularly in Latin America, which are supplanting the progressive ideas of left-wing authoritarians, is fostering a climate of distrust among groups of people.

Nevertheless, all is not lost. The darker the atmosphere, the brighter the small lights shine through the cracks in the pretentious and odious walls that separate those within from those outside.

In recent decades, the American continent has given us more than one message about the possibilities of human brotherhood. For reasons of personal whim and affinity, I will mention but three of them.

Americans to the World

Recently, I heard a joke that says the American continent has given the world 4,000 varieties of potatoes (papas). But since 2013, it has given it 4,002. This wisecrack, of course, refers to Pope (Papa) Francis and Pope Leo XIV. Men of faith and leaders of the Catholic Church, these men have invited us by their example to build bridges, not walls.

Francis chose to live as an immigrant in the Vatican. After being elected Supreme Pontiff in 2013, he decided not to change his citizenship and continued identifying himself with his Argentine documents. And this is not a reaction to the jingoistic displays we are apt to indulge in around here. This gesture, that of being a migrant like his grandparents, cannot be viewed as separate from the rest of his pontificate, which included, in its early days, a mass in Lampedusa, using as an altar the remains of a shipwrecked boat on which several unidentified people from Africa had lost their lives while trying to reach an opulent, indifferent, and contemptuous Europe.

As for him, Leo XIV gave us a very concrete gesture before his arrival at the Chair of Saint Peter. More than two decades as a missionary in Peru have left the Chicago-born Augustinian monk with not only perfect Spanish but also a passport. Because choosing another citizenship is not news. But choosing one from a country with typical Latin American problems, like Peru, despite holding the most powerful and coveted passport in the world, certainly is. Robert Prevost chose to throw in his lot with those living on the existential fringes of society. We can say that, by doing this, he became a true American and not just an “American,” that somewhat conceited and decidedly insolent term that those from the United States employ to refer to themselves.

The Question of the Individual

Thirdly, I cannot fail to mention this writer, as I am in my library, surrounded by his books and portraits: Jorge Luis Borges, who believed not only in the capacity of literature as an instrument of human happiness.

Author of stories like The Aleph or The Circular Ruins, he also attributed to literature the ability to be a vehicle of the imagination that could alter memory and, in so doing, have the power to modify the past, present, and future.

Borges' work also highlights the paradox that history is written from the physical impossibility of accessing the Truth. Therefore, history books and biographies are no more than the fiction of those who write them. Obviously, this historical impossibility also renders memoirs and autobiographies fictional. Disbelieving in the possibility of writing history allows us to question the imposition of national and patriotic myths. Ultimately, it enables us to free ourselves from the ponderous chains of identity.

But homeland and identity are not bad things, Borges muses. Neither are they necessarily good. The mistake would be to believe that one national identity is superior or better than another and that an individual, by the random chance of being born on one side or the other of one of those imaginary lines “so dear to cartographers,” is the bearer of a better identity than anyone else. In any case, patriotic fervor is also a personal choice. Borges always expressed an Argentine sentiment, but one rooted in the universal. It was not for nothing that he listed more than one homeland and recognized Buenos Aires, Texas, and Geneva as such.

Borges, a literary genius and master of words, but with the strengths and weaknesses of any other person, revisited a topic that, in Argentina, Leopoldo Lugones had already contemplated: The conquest and evangelization carried out by Spain made us heirs to Rome, Greece, and Israel. Therefore, citizens of the world. Men and women who could choose one nationality or another, an established patriotic myth or invent a new one, but who could never fail to be united by something inalienable: humanity.

The Moon Is Not So Far Away

Who can claim to be purely Argentinian, Guatemalan, or Brazilian these days? What country in this world has not been changed by territorial conquests or population shifts? Humans and culture have always moved around ceaselessly. Hasn't the English language undergone changes, and does it have the same identity and culture as it did in the Victorian era, or during the Cromwellian Republic, or in the time of William of Normandy? And what about Colombians? Are there no differences with the people of Bolívar's time? And what about those people who, nineteen millennia ago, left pictograms on the cave walls of Chiribiquete?

In the poem of the same title that closes his last book, The Conspirators (1985), which in some ways marks the end of his work and symbolically of his life, Borges wrote that a group of people “of diverse lineages, professing diverse religions and speaking diverse tongues” were conspiring and had made “the peculiar decision to be reasonable.” This, as the writer understood, was “to leave aside their differences and emphasize their similarities.” “Tomorrow,” he wrote, “they will be the entire planet. It's possible that what I say is not true, but I dearly hope it is prophetic.”

Today, the resolve to be reasonable seems even more peculiar. But once, it also seemed strange, unfeasible, even impossible to fly to the Moon.

— Translation from Spanish by D. P. Snyder

BIOGRAPHY

ESP. Juan Francisco Baroffio es escritor, ensayista y bibliófilo. Ha realizado cursos de literatura en Harvard University y de Filosofía Política en Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II. Diplomado en Cultura Argentina (CUDES). Ha publicado en diversos medios de Argentina (Infobae, La Nación, Todo es Historia, entre otros). Autor de Cuentos para la chica del abrigo rojo (2018) y El Restaurador: Juan Manuel de Rosas entre la mitología y la realidad (2019). Sus cuentos han sido publicados, también, en diversas antologías. Es colaborador del Festival Borges y miembro de PEN Argentina. Gran parte de su producción actual se dedica a la obra y pensamiento de Jorge Luis Borges. Director y co-fundador de la revista literaria Ulrica Revista.

ENG. Juan Franciscoscio Baroffio is a writer, essayist, and bibliophile. He has taken literature courses at Harvard University and political philosophy courses at the Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II. He holds a diploma in Argentine Culture from CUDES. He has published in various Argentine media outlets (Infobae, La Nación, Todo es Historia, among others). He is the author of Cuentos para la chica del abrigo rojo (2018) and El Restaurador: Juan Manuel de Rosas entre la mitología y la realidad (2019). His short stories have also been published in various anthologies. He is a contributor to the Borges Festival and a member of PEN Argentina. A large part of his current work is dedicated to the writings and thought of Jorge Luis Borges. He is the director and co-founder of the literary magazine Ulrica Revista